THREE STEPPS TO … (part 2)

The continuation of my first whisky job. Part one is here.

We pick up the story as the bottling line was getting ready to close down for the Glasgow Fair.

Parental Advisory information. There are robust adult words and drug references contained within.

The account is of a time long before the days of responsible drinking. Those of a sensitive nature should head to the tasting section.

As the Fair drew closer, so the talk began to be les about football and more about Benidorm and Alicante. The drinking also seemed, somehow, to increase. One day, two of we fuckinstudents were sharing the Gordon’s lines with a full-timer called Billy who had been showing the effects of extreme spelling since the early morning.

After lunch, he didn’t return from his spell. We worked on, expecting him to stagger out. Then the word came round that he’d passed out in the bog. We worked on. A brown coat appears.

“You not on your spell?”

“Just been.”

“You sure?”

“Aye.”

Behind the brown coat’s back, I could see Billy being stretchered out on a flattened piece of cardboard. The two of us ran the lines all afternoon. Collapsed at the end of it, but also appeared to have passed a test.

We students were tolerated, but we were never part of the workforce. The fact we paid no tax was resented, especially at the end of the week when the fat little envelope of notes was handed out. “Work less than we do and they get mair money.. fuckinstudents.”

On Fair Friday, after a morning of drinking I was summoned into a room where a white coat dispensed my first (and last) official dram. “Thank you David,” he said, handing me a glass and my wage packet. I knock it back, quite the drinker now, and head back to the bog where a fellow student has sparked up a joint. It was that kind of place.

The plant is packing up at lunchtime and I stagger to the bus, trying not to spin out as the two drugs compete for supremacy. Make it to the bus station and change onto an 11. By the time we’ve reached Woodlands Road I’m fighting growing nausea. The bus stops. I rush out and vomit up a close. Wipe the mouth and head into Lost Chord to browse the second-hand records and reggae imports.

Fair Play

The lines shut down during the Fair, so we were all sent outside. Some lucky bastards got painting, which seemed to consist of playing football with the paint pots as goalposts. The rest of us were at Despatch under the tutelage of Big John, a filthy-tempered man prone to cursing and full of wild tales of reckless debauchery.

“Where ye frae son?”

“Kelvindale.. you know…west end”

“Posh bastard.”

“Not really…” I start the explanation that it’s not Kelvinside. He’s not listening.

“Ye been tae the brothel in Park Street? Fuckin brilliant place…”

“Can’t say I have John,” says I, dreading that he’s going to invite me on his next excursion.

It was Big John who taught me how to pack a shipping container. Using a pallet truck was tricky enough, involving nasty little turns, but it was infinitely preferable to building by hand. Hundreds of cases rammed in from floor to ceiling. Containers may look perfectly rectangular, but they’re always out of whack.

“Right you. Get it right in the fuckin corner. Slam it in!” I do.

“Now build it.”

It’s going fine until the third row when, as the container is out of true, the cases won’t fit.

“What you stopped fur?”

“It won’t go John.”

“Kick the fucker then.” I poke at the box with my toe.

“Naw. Batter it! Gie it laldy son!”

He demonstrates. I hear the crack of breaking glass, the stain of whisky blooms across the white dog.

“Does it go noo?”

“Aye.”

“Right ye are.”

“But..”

“Listen son, “ he says, “All of this is bound for…” he looks at the case. “Venezuela. You really think they Venezuelese’ll be bothered by a few fuckin’ bottles broken in transit?” Another lesson learned. From then on we chucked them in. Kicking, stamping, hurling them against the sides to get a true fit, bathing in the fumes.

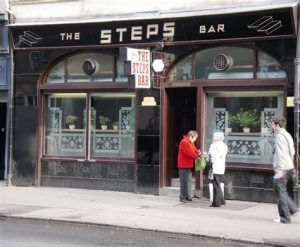

What I wasn’t doing was writing, though that had been the idea. Make some money, head to the hills, get away from the city. Instead, at the end of the shift I’d get the bus back to Buchanan Street and walk straight to the pub. Dram and a Fowler’s Wee Heavy.

I had begun to spend more time around Glasgow Cross, the Scotia, the Viccy bar, the licensed bunkers with breeze-blocks for windows and tables screwed to the floor. Pints and wee fat glasses with a quarter gill in them. Old Glasgow. My Dad’s workplace. Trying to find him by propping up the bar after work. Chewing the fat.

Was this the maturity that they were all talking about? If I was as mature as they said I was, then I was independent, and pubs, concert halls and friends’ floors were my new homes. This wasn’t so much rebellion as rejection of what had (or hadn’t happened) before, of social niceties, of silent Sundays, of church.

The area where I was brought up was, like many outlying parts of Glasgow, dry. Though there was a nice wee primary school and a row of shops, it was a desperate place for a teenager. If I wanted a new life, wanted to create, then I had to find it in the city, wander the streets. That summer I became Glaswegian, then turned my back on the city and never returned.

The exam results weren’t great, but were good enough to get me a dizzying 30 miles north to Stirling. I’d go back to Stepps the next summer before other jobs filled the summer break: a raspberry freezing plant, a clothing warehouse, then life took over.

It would be too glib to say this is where ‘my whisky life’ started. This was a job I chanced upon or, to be more accurate, was the result of nepotism. Neither did it show me a career path, or inculcate a deep love of the complexities of malt and grain. There was no epiphany, no Damascene moment as scales fell from my eyes and I could see clearly. Let’s face it, I could barely focus most of the time.

Yet, something happened that summer, maybe in the toilet, maybe in the endless wanderings round Glasgow, maybe in the pubs shrouded by cigarette smoke, drinking stale beer and haufs.

What that Stepps summer taught me was about community and how, though I could observe it at work, I could never be part of it; that if I wanted to walk and look and write, then being outside it all, being sat in the corner at a scuffed table with a notebook and a half-full glass was the way it would have to be.

This strange recalibration of self, this state of no-mind acted as some sort of seal. The healing would come later.

The Stepps bottling hall was closed in 1986 with the loss of 436 jobs. There were questions in the House of Commons, though I suspect there was an element of self-interest in the apparent concern expressed by Tom Clark MP for Monklands.

‘… it will come as no surprise to you, Mr. Speaker, or to the House, to learn that these men and women produce the whisky which, for many years—suitably labeled—has been sold in the Refreshment Department of the House. I, for one, have never heard any complaints about the quality of that whisky.’

Part of the reason for the closure of such a modern plant, it is alleged, had to do with serious financial irregularities. I had left long before.