Have some Madeira m’dearies?

It was, let me check, oh, almost a whole year ago that I wrote (some may say moaned) about the importance of knowing provenance of casks. I’ve posted it here. Its vague memory emerged from the shadows after I’d tasted the second of two rather toothsome Madeira cask whiskies recently, one from Bunna’ the other Glen Moray.

Madeira is a style that, when controlled, seems to fit Scotch nicely – sweeter than sherry, yet savoury, less punchy than Port. As with the irritatingly anonymous ‘sherry cask’ there’s often a distinct lack of information about what kind of Madeira the cask had been filled with. [Glenmorangie and James Eadie are exceptions to this]

When you look at it from the winemakers’ point of view, using the generic ‘Madeira’ is somewhat dismissive. It’s as if the wood had just been bought in a job lot. ‘We’ll give it a shot, see what it’s like’. (I’m sure that is far from the truth of course).

Perhaps I feel this more keenly because I have a deep and abiding love of fortified wines. My chum Big Chris and I have long planned a book called Fortification! [the exclamation mark being part of the title, you understand] though it’s come to naught.

So, here’s a quick guide. Madeira comes from the island of the same name. Like Port, the wine it is fortified before fermentation is complete leaving some residual sugar. How much will depend on the grape variety and style produced. Some are allowed to ferment for a week, but richer styles have it stopped after 24 hours.

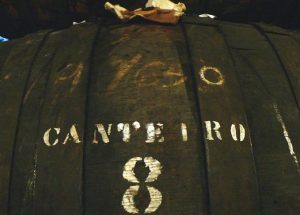

Traditionally, it’s matured in a slightly unusual technique known as canteiro. The fortified wine is put into American oak casks (varying in size from 300 to 650 litres) which sit in the warmest part of the lodge – up in its roof space.

There it will sit for four years, its flavours concentrating and, because the casks are not fully filled, slowly oxidising. After this initial ‘cooking’, the wine is decanted to casks in a lower (and cooler) floor and so progressively over the years to ground floor level where ageing can then be completed. Think of the old style way of rotating barrels in Bourbon.

The result is a wine with rich almost smoky black (and dried fruits), mixed with nuttiness and spice.

A simpler method of ageing, used for young expressions and blends, is to hold the fortified at between 45 -50˚C in ‘estufas’, stainless steel tanks with heated water jackets, for three months. It can then be transferred into casks, or larger vats.

To add another layer of complexity, it can be made from six different grape varieties, each with its own personality. The younger Madeiras are made from the most widely planted variety, the red grape Tinta Negra. This gives a mix of red and curranty black fruits and is usually pretty sweet.

The other varietals are white and used for the higher quality and longer aged wines which are some of the greatest you will ever try.

Sercial is light bodied, dry and intensely acidic. Almonds, apples, citrus fruits. It lasts forever.

Verdelho is medium bodied and can be found in medium-dry or -sweet. Here you’ll find more citric elements, figs, toffee and dried fruits. The acidity is still there though,

Bual is more perfumed and medium sweet with raisin, prune, some caramel, and a balancing citric bite.

Malmsey is the richest and sweetest style. There’s spice, more overt dried fruit, a hint of honey, while the citrus has turned to marmalade.

Madeira can be young, and blended, or single varietal. In turn, these can be bottled as single harvest at between 5-10 years, Colheita between 10 and 18 years, or Vintage, aged in excess of 20 years.

After all that, what exactly is a ‘Madeira cask’? Is the distiller using canteiro casks, or those used for estufa treated wines? If the casks are old they will be low on wood extractives, but soaked with decades of Madeira – but which type? If they are made for the distiller and seasoned, then what with, and for how long. Is the oak fresh or used? All of this will impact on the flavours which will come into the whisky.

Knowing Madeira in depth isn’t just about greater transparency for the consumer. It is giving a deeper level of understanding for the distiller/blender, allowing them to explore flavour.

Who knows, it might just get us drinking more Madeira as well. Win-win.