The Weekly Mash, Friday May 29

Hello folks. Hope you’ve had a good and fruitful week. The latest mash looks at two venerable whiskies (60 and 70 years old) and thinks on the difference between age and maturity. There’s a funky wee Raasay from Hedonism, the imminent return of The Liquid Antiquarian… and walk on parts for Tyshawn Sorey and King Tubby (but sadly not at the same time).

Read on, and if you like tell your friends…

Age v Maturity

I don’t know about you, but it’s uncommon for not one but two extra-aged whiskies to be sent for my attention in the same week. The arrival of the final release in Gordon & Macphail’s Mr George Legacy Series – a 70 year old Glen Grant – came through the door at the same time as a sample of House of Hazelwood’s 60 year old Girvan grain. Spoiled. I know…

The initial response is to marvel at their age. The decades spent in wood amaze us, and so the conversation will revolve around their venerability. They are reduced to numbers. There is however a difference between age and maturity. The time spent in cask is linear, from birth to bottling. It can be marked by years. It tells us how old a whisky is: 5 years or 50. But that is all it is. It tells us nothing about the liquid itself.

If age is a straight line, then maturity is curved. It is an arc, filled with influences. A river if you like, eddying, pausing, accelerating, rising and dipping. Maturity is never a straight progression, but moves organically. It is multi-dimensional. Maturity is character.

Knowing how to chart this dance between spirit, oak, and air is the whisky-maker’s greatest skill. It is functional: what type of cask, how many fills, warehouse conditions, and creative. It is also creative, the result of an intuitive understanding of how flavour and character develop, as points on that arc, how to understand the shifting balances between those three elements within the dance.

Oak can help, oak can dominate; air can add layers and texture, or flatten; spirit can dominate, or relax. Old whisky can be astringent or exhausted. Young can be aggressive. Equally, both can be balanced and characterful. Age doesn’t matter. character does. Achieving the balance is the skill. Why then the obsession with age?

And so to the pair in front of me. Both are excellent examples of advanced maturation, but in different ways.

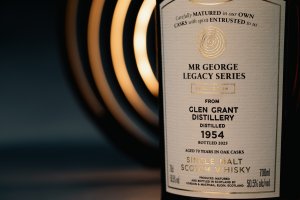

The 1954 Glen Grant is the last in a five-strong series (all from the ’50) from G&M paying tribute to George Urquhart, ‘the father of single malt Scotch whisky’. Two of the previous releases were reviewed here .

The House of Hazelwood Girvan was laid down the year after the distillery’s founding by then joint MD Charles Gordon. Its release is the start of an ambitious project to release a 100 year old whisky. The first release is of 25 bottles, and every decade for another 40 years an ever-older (and mature) expression of the same whisky will be released, with the century-old Girvan emerging in 2065, by which time I’ll be long gone. I’ve written about it (the whisky, not my death) in more detail here.

Girvan, 60 years old, ‘One For The Next’, House of Hazelwood, 50.1%

Single malts are about the individuality and, like people, can become grumpy when old. Grains on the other hand are amenable, suave. They pick up depth as they mature and start to glide along the river of time. They, rather than malts, are the key to a great old blend’s sophistication. The lightness of the spirit allows oak to play more of a role but, intriguingly, in the best examples it is absorbed rather than dominating. The distillery character emerges more fully over time. There is subtle strength at work here.

The smell of old grain whisky is fascinating. There’s a sweetness and ripeness here but allied to a refined mature character, helped by light oxidative notes. There’s butterscotch toffee, light oak, a grating of sweet citrus peel. Then comes Bounty bar, honeysuckle, flaked almond and sultana, before dried peach and marzipan emerge. There’s no loss of depth when a drop of water is added. Nuts emerge along with greater creaminess, light cherry. It seems to stretch, becoming brighter and almost vinous.

The palate is pillow soft. Cream buns, more of the sultana sweetness and clinging fruit (tinned peach juice), a little ripe banana, then coffee butter icing. Things become more honeyed by the middle of the tongue. Soft and sweet, but there’s enough freshness to carry it onwards. See you in a decade.

Glen Grant 1954 (70 year old), Gordon & MacPhail, 50.5%

Unsurprisingly for a whisky matured in a first-fill sherry puncheon, this is deep mahogany in colour. Rich, mature with distinct smoke, there’s also liquorice, wet coal, espresso crema, walnut, and a growing petrichor element. In time there’s a mix of iris, hawthorn jam, Unicum and a suggestion of mushroom. Dried dark fruits emerge with a droplet of water, but it’s still forested, complex, alive and seething.

Readying for the first sip, you’re anticipating density, but instead there’s fruit of the tropical variety (mango, guava) and only a light grip – though things dry at the end. It’s a fascinating contrast between earthiness, smoke and tea-like tannins with this purity of fruit.

Not for the first time, I’m looking at these as being aligned to seasons and place. The Girvan is relaxing in the summer sun, the Glen Grant is autumn beech woods, sunlight filtering through the burnished leaves. Earth and air, darkness and light. Contrasting balances, but balance nonetheless. Like any great whiskies they demand that you take your time. The reveal is slow, as it should be. There’s none of the hectic eagerness of young whiskies babbling all of their feelings to you in a rush. These offer glints and glimmers.

Perhaps you also take your time because, though you’re trying to ignore it, there’s a taxi meter running making the cost of each sip. You’re not going to waste it.

Recently, I was reading an interview with the American jazz drummer and composer Tyshawn Sorey in which he was talking about the role of time in music.‘I’m always viewing myself as decorating a home…That’s how I view temporality; the decorating of time. You’re only given this one chance to do that. You’re only given this one opportunity to envelop the listener in this space, where they have this finite amount of time to walk around the space and observe what’s in it, what it smells like, the temperature … What do they notice? What is there beyond the surface? When I say “the decorating of time,” that’s what I’m more-or-less referring to.’ Music and whisky both play with temporality and its effects.

Then the quotidian world crashes in, and that meter comes into focus. The calculations of age have come into play.There are only 25 bottles of the House of Hazelwood Girvan, 130 of the Glen Grant. The former costs £10,000, the latter £8,000. I am privileged to try these. Once sold, will they ever be tasted? Will they sell is another element to consider. Both are parts of series, and legacy projects – for Charles Gordon and George Urquhart. That should be enough to pique the interest of true (and well-heeled) collectors who care about liquid not packaging.

However, this rarified end of the market is tough at the moment. Expensive bottles are sitting on retailers’ shelves. They in turn aren’t stocking new top-end releases unless a sale is guaranteed. The cabinets of the rich are filled, prices in the secondary market are falling, investment scandals are scaring off speculators.

Many firms are retreating from the premiumisation of the past decade or so. It used to refer about consumers trading up from, say, Walker Red to Black. Then it was Black to Blue, then Blue to King George V, etc. In malt it was 12 year old, to 18, then 20+, then ever onwards. Now, £50-£70 for malt is the key price band. Whisky will always be premium in some respect. Spending £50 on a bottle is a luxury to most drinkers. What firms are now doing (or should be doing) is redefining what ‘premium’ is.

Time passes but movs in cycles. We rise, we dip, we return, we build again. The market, the whisky.

———

In My Glass

At the other end of the age (and price) scale is a bottling of Isle of Raasay by Hedonism Wines & Spirits. Its Raasay Peated Sherry, 2021 (59.3%) comes from a quarter cask and is bottled at 59.3%. It costs £85.

The quarter cask’s size means that, even after only three and half years of maturation, there’s been a big uptake in colour. The smoke is prominent, but held within a mix of dark, sugary sweetness alongside Nocino, black cherry and Brazil nut. There’s a vegetal , mossy quality that pushes towards decomposition, then walnut whip and a cow byre undertow. Delicious, funky, fruity, and smoky.

Quarter casks will give big impact quickly, so you lose immaturity and gain oakiness, but the issue often is a lack of integration between the spirit and the wood – it’s why air is important in maturation.

Here, though, there’s balance and integration: sweet dried fruits, cherry liqueur, dark chocolate and a bacony element whose fats add texture and sizzle. Better get clicking, there’s not much left.

———————

A-musing

Permit me, dear reader, a moment or two of shameless self-promotion. My dear friend Arthur Motley (late of Royal Mile Whiskies) and I have alternative lives as antiquarians. We’re not historians, but enthusiasts who like rummaging around in dusty places, finding out new stories about old drinks (mostly whisky and rum so far, though mangelwurzel spirit seems to pop up with bizarre frequency).

We then chat about our discoveries and theories on our YouTube channel, The Liquid Antiquarian.

It’s been on hiatus for a while, due to life, but is about to return with more revelations. The aim this time is to give it a dose of prune juice and make it regular. Stay tuned – there’s some crackers upcoming. In the meantime, all the previous episodes are available on the link above.

———-

In My Ears

Dub is always there or thereabouts. This week I’ve paid a return to Tubby’s with the compilation Dub Gone Crazy – impeccable sound manipulation