The Weekly Mash, Friday 8th August

Hello campers! After last’s week’s look at shape tasting, this Mash is a roundup of some of the latest whisky books, plus a brace of Wolfburns and a beastly Ardbeg. Enjoy, and have a great weekend

On My Bookshelf

Whisky books come in many guises – there’s the tasting book, the history one. They can focus on distillery profiles, act as beginners guides, or aim squarely for the geeks. Some might focus on a single brand, topic, location, or style. It’s not surprising. The complex nature of the spirit and its stories dictate that there are numerous angles for writers to explore.

One of the most individual approaches was that taken by the novelist Neil M. Gunn. He knew his whisky, having spent 26 years in Customs & Excise, initially as relief for the distilleries in the northern Highlands, and later on-site at Glen Mhor in Inverness.

‘Whisky and Scotland’ was written in 1935. Its subtitle, ‘A Practical and Spiritual Survey’ gives a clue of what lies within. Only half of the book is directly about whisky (formation of the industry, production, recommendations). The rest is a mix of polemic, myth and politics – specifically Scottish independence. For Gunn, whisky is Scotland.

He’s distinctly sniffy about grain whisky and blends, saving his praise for single malts, a drink which he calls, “as noble a product of Scotland as any Burgundy or Champagne is of France.”

Among his tips is a Glen Grant, “bottled by a firm in Elgin [which] carries a label ‘matured in sherry wood for ten years,’ but his heart belongs to Old Pulteney which, “when well matured [has] some of the strong characteristics of the northern temperament”.

Though his approach to whisky’s origins might give serious historians an attack of the vapours – Druids are involved – at no point is he saying his fantastical story is true. He’s a novelist imagining how the first person to try and distilled spirit might well have reacted.

Whisky ran through his life and writing. In 1937, having just resigned from the Excise to become a full-time novelist, a long dram-fuelled ceilidh on Skye resulted in him buying a less than seaworthy boat. He set off with his wife on a three-month voyage around the Inner Hebrides [recounted in ‘Off In A Boat’], only to be immediately forced into Portnalong with engine trouble. The upside of this was that he was only a short walk from Talisker.

In the 1950s, he was hired by Lord Bracken to tramp the hills above Cromdale to find a water source for what would become Tormore [a Gunn bottling surely is required].

The spirit also seeps into his stories and essays. At the end of his life, when he’d become a Zen adept, Gunn was still linking whisky with the world of myth, rooting it in experience and place.

‘I do not know the description of the taste of an Orange Pippin has ever been caught in a phrase,’ he wrote in his autobiography, ‘The Atom of Delight’, ‘but we had our phrase for [hazelnut]… and it was “whisky taste”. The crack … the mash, the mashing of the mash until with the help of a generous spittle the whole attains that degree of liquidity which frees to the full the ultimate flavours the quintessence of whisky taste.’

As I wrote in ‘A Sense of Place’ [still available folks] ‘He’s linking ‘whisky taste’ with the nine hazel trees of Celtic myth which surrounded the well of knowledge. When the nuts fell into the pool, the salmon of wisdom ate them… and when Fionn ate the salmon he gained wisdom and the knowledge of poetry. Whisky taste at the heart of it all.’

Anyway, ‘Whisky and Scotland’ has just been reissued by Souvenir Press as a paperback. If you haven’t a copy, it’s well worth your £12.99. The only criticism is that a reprint of such an important book deserved a foreword – ideally penned by Gunn scholar Gavin D. Smith.

A lovely example of a single topic book appeared recently. ‘Opening The Case: The Affairs of Pattison’s Whisky’ [Self-published, £19.99] by Justine Hazlehurst is a much-needed and fascinating account of the Pattison Crash which brought the Scotch whisky market to its knees in the late 19th century.

A lovely example of a single topic book appeared recently. ‘Opening The Case: The Affairs of Pattison’s Whisky’ [Self-published, £19.99] by Justine Hazlehurst is a much-needed and fascinating account of the Pattison Crash which brought the Scotch whisky market to its knees in the late 19th century.

It’s a topic that’s mentioned in passing in many whisky histories, but is one which has never been explained in such detail as it is here. By using primary sources, Hazlehurst not only examines the hubristic, not to say illegal, financial business activities of the firm, but allows the Pattison brothers themselves to come to life. It also places the affair within the wider context of Leith’s almost forgotten role in whisky.

For those of you with an interest in whisky history, it is a must-have. For others who want to read a family saga filled with nefarious goings on, dubious financial practises, an unpaid tailor … and parrots, then you’ll find plenty to enjoy.

It’s been joined by two hefty tomes, each of which could stun a charging sheep. By some strange coincidence, both sport similarly chocolate-coloured covers. Maybe it’s the new thing.

Felipe Schrieberg is one of the smartest of the new(er) writers about whisky – his work on dodgy cask investment schemes deserves high praise. ‘The World of Whisky’ [Cider Mill Press, £30] is his first BIG whiksy book and, as you’d expect, the writing is excellent.

Felipe Schrieberg is one of the smartest of the new(er) writers about whisky – his work on dodgy cask investment schemes deserves high praise. ‘The World of Whisky’ [Cider Mill Press, £30] is his first BIG whiksy book and, as you’d expect, the writing is excellent.

It’s a handsome, lavishly-photographed run through of key distilleries around the world with interviews, profiles, and a ‘must try’ for each entry, some of which also have a featured signature cocktail.

With a section on the basics of production, a riff on histories and up-to-date thoughts on where whisky is heading, it covers all the bases. Ideal to slake the thirst of newcomers.

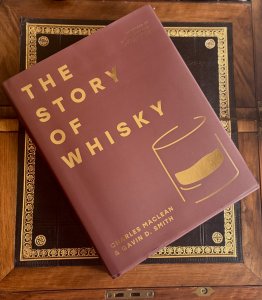

Charlie MacLean and Gavin D. Smith have slightly more books under their belts than Schrieberg, but this, I believe, is their first collaboration. ‘The Story of Whisky’ (Pavilion, £45) does what it says on the cover.

Charlie MacLean and Gavin D. Smith have slightly more books under their belts than Schrieberg, but this, I believe, is their first collaboration. ‘The Story of Whisky’ (Pavilion, £45) does what it says on the cover.

The book is divided chronologically into five sections, taking you through whisky’s story (or to be precise distilled spirits’ as it starts in 1200BCE) with short essays on people, distilleries, location, business, equipment, books and general ephemera, each acting as a rabbit hole to dive down.

A subset of the ‘around the world in 100 objects’ genre, it’s a book to leaf through in order to discover intriguing nuggets with which to increase your knowledge and impress your friends. The authors’ knowledge is worn lightly.

———————————-

On My (Drink) Shelf

Wolfburn has just reduced the price of their 10yo and added a new 12yo as a permanent member of the core range. How do they compare?

Wolfburn 12yo (46%/£69.99)

Wolfburn 12yo (46%/£69.99)

A shade lighter in coliur this has been aged in a mix of ex-Bourbon and oloroso casks. There’s more of the distillery’s fruit here, mixing red fruits, honey and creamy sultana (Queen of Puddings?) A dry, bracken-like aroma appears over time, along with hazelnut and light toasted oak.

It’s gentle and broad with a mix of melting milk chocolate and date. It flows on to the mid-palate adding in a vinous, almost slippery, quality alongside blackcurrant. There’s a hint of a crème brûlée with a burnt top before spices start to fizzle on the back. Worth a look.

Also tasted

Wolfburn 10yo (46%/£66.99)

Wolfburn 10yo (46%/£66.99)

You’re greeted with a mix of fresh pear, dessert apple mixed with the tweedier side of sherry casks. There’s pecans cooking in brown butter, some figs and as it opens, there’s an almost savoury note. Water brings out deeper aromas, old apples, and dark chocolate.

The palate is soft from the get-go with, for the first time, an indication of the brightness of youth. The fruits sit here. As it broadens in the centre, there’s a bready/nuttiness alongside walnut. A fat mid-palate (it’s a reverse hourglass shape) stirs in dried fruit, a little smoke/char, and a growing gingery spicy attack.

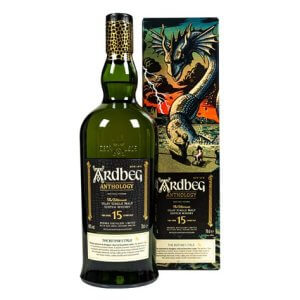

Ardbeg 15, The Beithir’s Tale (46%/£135)

Ardbeg 15, The Beithir’s Tale (46%/£135)

This is the third and final member of a trilogy of Ardbegs named after mythical (?) Scottish beasts, in this case the Beithir, a ferocious water serpent which has a poisonous spike on its tail.

All three are part of a project aimed at showing Ardbeg’s sweet side. If you were to strip away Ardbeg’s smoke you’d reveal a sweet core which is vital for balance. Pulling this forward is an interesting endeavour, as long as in doing so you don’t lose any of the distillery’s Ardbegginess.

This has been aged in the air-seasoned, heavily-toasted lightly-charred ‘bespoke’ casks used at Glenmorangie. Overall, the aromas are light but true to its aim it starts sweet, though there’s also the dusty smell of a soot sack, some coal tar even a hint of (sweet) leather. This in turn is contrasted with custard slice and toasted coconut (a smoky Lamington?) There’s a touch of wakame (dulse) and, with water, a green herbal note.

There’s dry smoke straight away on the palate which lifts wispily towards the top of the mouth while the creamy vanilla bobs along underneath. Again, there’s green notes (creosote-coated garden twine, dried tarragon, burnt lime, charred lettuce).

Overall, its narrow and short, with none of the dense oils which typify Ardbeg. Pimentón and chocolate appear on a sweet finish that hints at grapefruit, then flattens. It’s all there, though the total effect is oddly muted. A walk of the sweet side? Yes, so job done. A ferocious water dragon? No.

In My Ears

The new release from caroline (called, accurately, caroline 2) is a refining of their undefineable sound. Is it folk, post-rock, improv, left-field pop? Yes, all of these, often at the same time. Their music seems to teeter on the brink of collapse, yet somehow it holds together beautifully. It’s music that’s a blessed alternative to the return of the Rutles rip-offs from Manchester. Is that a whisky metaphor? You decide … 😉