The Weekly Mash Friday 20th June

Greetings! A distinctly Irish theme this week with a look at single pot still, Samuel Beckett’s drinking habits, varnished tongues, a new Redbreast, updates from Micil, Boann’s marvel of a dram .. and the singing of Brigid Mae Power.

The Pot’s Boiling

Under a medical centre in Dublin’s Fitzwilliam Lane are two empty arched cellars, a silent symbol of the story of Irish whiskey. We’re in the heart of the city, next to Merrion Square, where the great, the good (and often not so good) lived, did business, played politics. A prosperous place, a prized address.

The cellars had once held the barrels, hogsheads, and butts of whiskey owned by Mitchell & Son Wine Merchants. All were daubed with different coloured paint: green, some red, or blue, or yellow each one signifying a different age.

The whiskey came from John Jameson & Sons’ Bow Street distillery, two miles away on the north bank of the Liffey. Mitchells, like all of Ireland’s many bonders, would age it in its own casks and sell it under its own label. So was born the Spot series: Blue (7yo), Green (10yo), Yellow (12), and Red (15). All were single pot still.

The empty cellars speak not just of Irish whiskey’s fall, but the (almost) demise of the style. By the 1960s, there were only two pot still whiskeys still available: Green Spot, and Gilbey’s Redbreast. For a time in the 1980s, only Green Spot was available with its thrilling mix of embrocation, pine resin, linseed oil and cut grass. A whiskey which caressed the tongue while also possessing an acerbic edge. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was Samuel Beckett’s dram of choice.

Single pot still is made from a mixed mashbill based on malted and unmalted barley with the former’s enzymes converting its own and the unmalted barley’s starch to fermentable sugars.

The myth is that it was created after the imposition of a Malt Tax in 1785. By using a mixed mashbill, distillers would reduce their tax burden. While this might have helped to make the style more widely made, mixed mashbills of some complexity were already commonplace prior to the Act.

By the early- to mid-19th century, Ireland’s urban distilleries had become substantial operations. All were making single pot still, a whiskey which was more consistent and of higher quality than the Scotch of the time – and the ideal, weighty base for the era’s most popular serve – the toddy.

Single pot still is oily, leathery, but also spicy. There’s soft fruits, blackcurrant leaf, as well as green orchard fruit (apple/pear). Rich and clinging, fruity, yet zippily acidic. It sticks on the tongue and in the mind. It is a whiskey that insists you take notice of it.

This golden age was not to last. By the end of the 19th century, palates were changing. Highballs were the drink rather than toddies. Ireland’s distillers now had to compete with a confident Scotch industry whose blends had been reformulated to take account of the Highball trend. The Irish pot still distillers stuck to their guns, but sales began to decline.

The bad news continued. Ireland’s gaining of independence cut off the British Empire market (then whisky’s largest). Supplies to the US during Prohibition were curtailed due to the major Irish distillers’ reluctance to indulge bootlegging (Scotch producers had no such qualms). Add in the Great Depression, an export ban imposed by the new Irish government, plus high domestic taxation and the Irish whiskey industry collapsed.

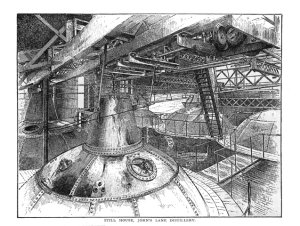

In 1966, the republic’s last three distillers (John Jameson, Power’s, and Cork Distillers) merged to form Irish Distillers Limited [IDL]. Jameson closed Bow Street in 1972, Powers closed its distillery in Dublin’s John’s Lane four years later. Production was switched to IDL’s new, purpose built distillery in Midleton, Co.Cork.

Single pot still was still made, but now as a component within blends (Power’s Gold, Jameson, and the still hugely underrated Crested Ten). If you knew where to look you could pick up Green Spot and Redbreast, but they were not priority.

Whisky, as I’ve said here before, is cyclical. By the 2000s, a new whisky consumer had emerged. One who wanted richness and power, who enjoyed exploring flavour. In 2005, IDL launched a new single pot still range.

Green Spot, Redbreast (the latter with a new 15yo expression) were joined by the mighty Power’s John’s Lane, a whiskey which left your tongue feeling varnished as a procession of almond, caramel toffee, saddle soap, black banana and damson jam oozed along. The trio was completed by the relatively restrained Barry Crockett Legacy with its apricot and peach syrups, stewing plum and melon.

Here was evidence that IDL didn’t just make pot still, but pot stills. The same mashbill, but different distillation regimes and cut points giving light, medium, and heavy styles – and intermediate weights.

What of now? The IDL range has continued to expand, while the best of the island’s new distillers are exploring Irish whiskey’s roots. The launch of Jameson in the bleak ‘70s was a sensible strategy – a mixable blend which could exist alongside, and much later compete with, blended Scotch. Now though, if Irish whiskey was to start afresh single pot had to be at its core.

What was single pot still though? In 2014, with the new Irish industry beginning to form, a Technical File was drawn up defining whiskey styles. As IDL was the sole producer of single pot still at the time, its recipe (a minimum of 30% barley, 30% malt, and a maximum of 5% ‘other grains’) was adopted.

This ignored the historic mashbills used in Ireland – including those which had defined the original Jameson and Powers styles where oats played a significant role, as well as rye and wheat. It was effectively restricting single pot still to a single recipe rather than embracing the fluidity which had existed in the past when every distillery had its own take.

Whiskey is good at ignoring its history and believing what is happening now is somehow tradition. The egregious misreading of single pot still was challenged by historian Fionnán O’Connor who, as part of his PhD thesis on Irish whiskey had researched historic mashbills. He then worked with Drogheda’s Boann distillery to make whiskeys from these old recipes.

It was the trigger for rebel distillers to start making ‘non-compliant’ single pot stills (which can only be labelled as ‘Irish Whiskey’) There’s been Blackwater’s Dirtgrain Project, as well as Killowen’s Barántúil series. Barley and malt as the base, but what about oats, wheat or rye? Why not malt them, or malt and peat them? Why not peat the barley? Why not change ratios dramatically and make oats the driver?

‘We owe this to our culinary heritage and to show that our distilling heritage is still alive’, Killowen’s Brendan Carty told me. ‘If Ireland is to succeed in whiskey it has to be through diversity, but ultimately it has to be through single pot still.We have a responsibility to put it right.’

Boann has a three-strong single pot still range [see below] but is also releasing single cask, non-compliant historic mashbill whiskeys each solstice from its collaboration with Fionnán.

A quarter of Ardara’s output is single pot still, made with a non-compliant recipe of 50% peated malt, 30% barley and 20% peated malted oats, in keeping with its Donegal tradition.

The same applies to Connemara, home to brothers Pádraic and Jimín Ó Griallais (who we met here) whose Galway-based Micil distillery continues a generations-old tradition of poitín-making (albeit legally in their case) as well as making single malt and two single pot stills,

They sent over two cask samples of the latter. One a compliant mashbill (50% malt, 45 barley, 5% oats) the other a heritage recipe (40% peated malt, 35% barley, 12% oats, 5% rye, and 8% wheat). Following Connemara tradition they’re aged in 50l casks.

The first (aged in PX) smells of a mix of floor polish, hot sesame oil, smoke, leather, nuts, red liquorice, dried cherry, and biltong. There’s turfy smoke and thick, black fruits on the palate. The heritage mashbill starts with sticky ooze from a fruit pie, mixed with leather, sandalwood, red fruits, and wax. The palate is smoky bacon, allspice, shaving lather and sour fruits. Neither are out yet – they need a little more time in cask – but are hugely promising and, like the other rebels, speak of the thrilling expansive thinking from this cohort of new distillers.

The days of non-compliance may soon be over. The Irish Department of Agriculture has indicated that it will not oppose changes to the Technical File which would allow up to 30% of ‘other grains’ being used in single pot still. The changes would then have to be ratified by the EU, but distillers are cautiously optimistic.

—————————

In the Cupboard

Redbreast 15yo Cask Strength (56.3% abv/£110)

Part of the reason for that long screed was the arrival of this wee cracker to the tasting table. It’s a limited edition cask-strength (hurry!) which is only available at MidletonDistilleryCollection.com and is a vatting of 15 ex-Bourbon and oloroso casks.

The oak influence is subtle, allowing the distillate to be the driver. There’s a mix of raspberry leaf, green grassiness/parsley stalk, nectarine and white pepper bound together with light oil (virgin rapeseed?) black banana and a nutty/yeasty element.

It has a bouncy texture, with blackcurrant, apricot, cassia, those thickening oils and then a classic drying spiciness with the mouth-numbing, citric qualities of Szechuan pepper. Water makes it creamier adding spiced cider and brings out a sweet red berry core. Excellent stuff.

————————

On The Shelf

Boann Madeira Cask single pot still (47%/£68)

One of a trio (the others are PX and Marsala), this is compliant, but still pushes at the edges of the current regs with a mashbill of 55% barley, 40% malt, 3% oats, and 2% rye.

It starts in ex-Bourbon and then goes to Madeira casks which on paper isn’t that unusual these days, until you realise that the Madeira element is drawn from the entire gamut of the island’s styles: Tinta Negro, Boal, Sercial and Colheita.

That means a diverse range of flavours to fold into the vatting, from sweet to bone dry, all with differing degrees of Madera’s electric acidity. This willingness to look beyond ‘Madeira cask’ or a standard mashbill typifies the New Irish thinking.

The nose has the elevated juicy fruits shared by many Irish whiskies plus some cooked apple, wild flowers, meadow hay, a glimmer of blue fruit. The silky, sticky pot still oils come though on the palate beside black fruits. It brightens and then tightens on the finish as spices and acidity combine.

—————————

In My Ears

There’s so much great Irish music about at the moment … Lankum, Lisa O’Neil, John Francis Flynn, Landless, Cormac Begley etc etc. and this week’s choice, the Galway-based, tradition-adjacent songwriter, Brigid Mae Power.

She is just one of so many creative women in Irish music, poetry, and literature whose voices are now, finally, being heard. Her most recent album [Dream from the Deep Well] is worth a dive into, as is this collection of covers [Songs For You] all linked to memories of her father.