The 100 Club

On April 14, 1963 the young Charles Grant Gordon, joint MD of William Grant & Sons, broke ground at what was to be the firm’s new grain distillery at Girvan. Amazingly, the first spirit flowed by the end of December the same year. Just think about what that means. An entire grain distillery, plus warehousing built on a brownfield site in less than a year. In fact shorter than that as the site had first to be cleared and the building didn’t start until August.

In the firm’s in-house Focus magazine, Magnus Magnusson called it ‘the Year of Havoc’, with the work running 24 hour a day in often horrendous weather conditions.

According to the account, Charles handed out 1,500 bottles of whisky as ‘incentives’ (presumably for consumption after the shift was finished). He would cycle round the site cajoling and urging on the workers. At the end of the build, someone stole his bike and welded it to the top of the stillhouse.

Charles was always known for his eagerness, but why the unseemly rush? In the early 1960s, the price of grain spirit was fixed at the start of the year – and production was virtually controlled by DCL who at the time had stopped supplying Grants.

A gentlemen’s agreement over the manner in which Scotch could (and more importantly couldn’t) be advertised was in force. No television advertising was to be permitted. This was as much to do with keeping DCL’s ever-warring blending houses in their place. Grant’s broke this rule – another of Charles’ ideas. The result was the DCL tap being turned off, leaving Grant’s short of supply for its then-growing Standfast blend.

The firm having its own supply of grain fitted with Charles’ belief in having control over as much of production as possible. The cooperage, coppersmith and on-site bottling in Dufftown are examples of this. According to Andy Fairgrieve, the firm’s archivist, the proposal for a grain distillery had been put to the board on a number of occasions, but had always been rejected.

‘Charlie would get an idea and put it into action,’ he explains. ‘The opinion of the rest of the family was that a supply deal was in place. Anyway, they were spending a lot of money on advertising, and the new triangular bottle, so there was no need for added expense. As soon as DCL began making noises to reduce supply that was ammunition enough for Charlie to go back to the board and say “now is the time”.’

After scoping out potential sites in Fife and the deep water port of Cairnryan (near Stranraer), a former Ministry of Supply site at Girvan owned by the local council became available. The council also threw in the incentive of a 30 year deal on water, levied at 1d per 1,000 gallons. A new business generating 200 jobs made sense for the Ayrshire town where unemployment was rising.

John Ross has worked at Girvan for 47 years. Now technical area leader (which means he is in charge of the firm’s technical innovation arm) he arrived at Girvan with no whisky-making experience. There have been considerable changes.

‘Up until 1978 distilling was on maize,’ he recalls. ‘It would arrive in Glasgow and the trucks would run 24 hours a day to Girvan. There was no creamed yeast either, it was all bagged. By then there were two stills. The original #1 Apps, and#3 Apps – we’re currently installing #7 Apps.

‘#3 could do grain neutral spirit, while #1 was a simple two-column copper still with an analyser and rectifier run on direct steam injection. It wasn’t a Coffey still though, as one of the three condensers was used to preheat the wash, rather than by a pipe inside the rectifying column.

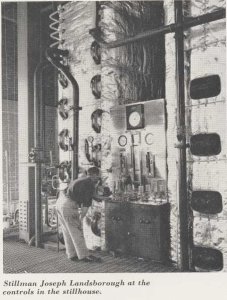

‘When I joined it was very much not automated. We relied on the skills, knowledge and experience of the operators most of whom would have been there from the start. A lot were ex-miners – the Ayrshire coalfields had begin to close in the mid-50s – so they had a lot of skills: fitters, electricians and all very safety-conscious.

‘They’d listen to the pitch of the steam in the analyser to check it was running correctly. We had density meters, but they’d only check the spirit strength with a hydrometer. They didn’t trust new-fangled automation. Even when I joined we were still building our knowledge.’

Some of the casks filled in those early days were squirrelled away and now, as part of the slightly belated celebrations of Girvan’s 60th year anniversary, form the basis of an extraordinary project from House of Hazelwood – the creation of a 100 year old whisky.

‘What’s distinctive about the Gordon family is that everything is about legacy,’ says Jonathan Gibson, House of Hazelwood’s director. ‘The current family members are driven by the idea of passing on something that is bigger and better to what was left to them. It’s not financial aspiration, but quality and reputation.’

While a bottling of a (very) old Girvan would have sufficed for most firms, Gibson took inspiration from a unlikely source. ‘I always like old school hip-hop. In 2015, the Wu-Tang Clan created a single CD, ‘Once Upon a Time in Shaolin’ which was sold on the proviso that it couldn’t be publicly released until 2103.

‘I liked this idea of creating something, then putting it away and protecting it – then listening to the compete work in 100 or so years. In many ways, it’s what we already do.

‘In whisky, we’re producing something today that is for the future. It could be in three years time, or 12, 50, or 100 years. It’s always about the future. This is at odds with some people’s mindset of buying a whisky then flipping it – treating it as a commodity.

‘We thought it fun and interesting to draw collectors into the mindset of looking after a whisky for a long time. They are part of the whole project.’

The House of Hazelwood’s equivalent to the Wu-Tang’s cd, is ‘One For The Next’. It consists of 25 bottles of 60 year old Girvan grain.

Every 10 years, another bottle of the same whisky will be released – as 70, 80, 90 and ultimately 100-year-old expressions. Those who have bought the 60-year-old will be granted first refusal of the opportunity to purchase these future bottlings.

There’s some practical considerations, foremost among them being how to control maturation of an already old whisky for another four decades. The 60-year-old is now being filled into custom-made, refill European oak hogsheads. They are stored in the, cold, lower floor of Grants’ Convalmore warehouse in Dufftown.

‘Old refill wood was essential,’ Gibson explains. ‘We want to see the evolution of the whisky’s character rather than the wood having much impact. We expect it to feel like the same whisky at every release. We wouldn’t be talking about it if we didn’t think it was possible.’

There is a degree of madness about this which I heartily approve of. It’s like the ‘On the Way’-style series we’ve seen from the likes of Ardbeg, Kilkerran, and Raasay as they moved to their first core release. This is at the other end of the age scale and has never been tried before.

It’s also a grain, which is both exciting and daunting. I can see people getting excited about a 100 year old malt, but a century-old grain is a tougher sell. Gibson is, however, undaunted.

‘It is an opportunity,’ he says. ‘Almost no-one has tasted grain whisky over 40 year old because old grain whiskies are the rarest kind of Scotch. Grain is used young in blends, so to get an example at this age is out of the ordinary.

‘When malt was first championed last century, a lot of producers could band together and make it work as a new category. Not too many of them are holding on to grains whisky of this age. We’re essentially doing this on our own.’

It is also taking a different tack to many of the whiskies in this rarified area. I chafe at the increasing number of top-end whiskies where the liquid and the packaging seem bolted together. Sometimes I get the feeling that the packaging (if that’s not too insulting a term to use) is more important than the whisky itself. It’s Marx’s “commodity fetishism” at work.

The ones which align pack, bottle, and whisky into a coherent story, where each element is inspiring and feeding off the others, work. Most these days don’t.

How then is ‘One For The Next’ different? The pack – a cabinet made with wood from a tree which grew in Hazelwood House’s garden is a link back to the story – and to Charles. The addition of a plaque on the cabinet with a personalised message to whatever generation will finally be able to taste the whole range, is a clever and human touch. Ultimately it, like the other House of Hazelwood range, is about legacy and family.

Conceptually then a fascinating idea, but the question has to be asked. Who, at a time when the top end market is suffering, will pay £10,000 for a bottle of 60yo Girvan? Some firms are pulling back from the extravagance of the luxury end to refocus on lower priced/aged offerings. There’s even rumours of private client divisions being scrapped. The market is changing, refocusing. A 100 year old whisky is a phenomenal idea, but who will buy into it?

It’s a brave move. It is also a very Charles Gordon one. ‘He had the ability to see what others couldn’t,’ John Ross told me. Is this generation blessed with the same foresight? Ask me in 40 years …

Full tasting notes and more thoughts on this and another exceptionally old whisky from Gordon & Macphail will be in the new Weekly Mash on Friday 30th May