The Weekly Mash, Friday 17th October

Last month, Number One Drinks released its final bottling of Karuizawa, the cult Japanese distillery whose remaining stock it purchased in 2011. Called Once In A Lifetime, it is a vatting of whiskies from the ‘60s to the time of its closure (and subsequent demolishing) in 2000. It was also the end of my own relationship with the distillery, much of which has been as a minor co-conspirator with the Number One team. It’s been quite the journey.

———————-

Before you reach the liquid you have to open the box. In a world of bling this is understated, a plain wooden container which, once you have cracked the puzzle of its opening, reveals an interior modelled on a Shinto shrine. Just as that contains the kami (spirit) of the place, so does this, both literally and symbolically.

Made by Hiroki Goda in his workshop in the forest above Kyoto, its front panel is made from an old Karuizawa stave. It’s not European or American oak, he says. Neither is it mizunara. Rather, he feels, it’s another type of Japanese oak. Karuizawa’s story is not straightforward and always surprising. Even in its final moments some new mystery emerges.

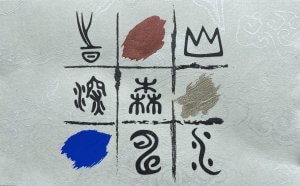

The bottle is simple as well, the same as the old Number One distillery bottlings. The label too is understated, a grid of nine with each square containing either a colour or a symbol. Each one tells a different part of the distillery’s story.

The blue brushstroke is for Ocean [the blend Karuizawa supplied], copper is for stills, gold for barley. The symbols are derived from ancient Chinese oracle bone script, the precursor to kanji: mountain, water, forest, time, angel, strong, time. They sit on a white washi paper printed with white clouds.

Each label was hand made by Toto Akihiko (Choemon), of the 500 year old karakami [decorative woodblock prints] house, Kira Karacho in Kyoto. ‘All of these hangi [woodblocks] have deeper meanings,’ he explains. ‘Gods and spirits reside within them.’ The spirit of the spirit.

Where did it start? For me, in February 2005 when I got off the train at Karuizawa station and headed to a strange looking distillery with buildings covered in vines. The warehouses were low, the distillery itself one room with a mashtun that reminded me of R2D2 and small stills whose necks curved into the rafters. The winter chill seeped in. Everything was cold, quiet. The bottles in the distillery’s shop had dust on them. I bought some for virtually nothing. Outside, puffs of smoke rose from the snowy peak of Mount Asama.

Nothing was being produced, not unusual for Japan in those days, but the plum blossom just emerging seemed to be a symbol of rebirth. Surely it would only be a matter of time before Karuizawa’s owner Mercian would reopen it. Even if whisky sales remained sluggish in Japan the country’s single malts were making waves in export. One visit and this strange, silent, sad place had me hooked.

It wasn’t just because of the location and atmosphere, but the taste. This was unlike any whisky I had encountered before. Each distillery I’d visited in Japan had followed a similar methodology of making multiple distillate streams, ageing them separately in a mix of cask types, then blending. Not here.

One way, one style. The result was thick, powerful, and strangely scented. It spoke of the earth, and the depths of a wood. Even now, 20 years later I’m still not sure if I have ever managed to fully define what Karuizawa smells like. It’s incense-like, autumnal, sometimes feral. There’s tamarind, aged soy, prune, tea, dried black fruits, and soot all bound together by some strange lacquer. The whisky equivalent of Antonio Stradivari’s secret varnish? A distillery which made this would obviously reopen.

Karuizawa seemed to exist in a parallel time stream, the last outpost of a older way of making single malt. Its adherence to old practise, the use of Golden Promise to add a thick, oily texture. The use solely (until its final years) of 100% ex-sherry casks. Behind others, but also ahead of most. The first distillery to import foreign barley. The first Japanese distillery to be bottled as single malt in 1976 when no-one really knew what that meant. It challenges the assumption that the distillery’s sole function was to provide filings for Ocean. The fact that the casks which Number One bought included whiskies dating back to the ‘60s suggests that there was a long-term strategy at work.

There is always a ‘what if?’ when you’re faced with a silent distillery. Everything here appeals to today’s geek: lava-filtered water, the barley, it’s own yeast strain, long ferments, heavy-bodied new make, an idiosyncratic variation on sherry casks, an aroma which sits beyond the conventional. What if …

It wasn’t to be. We know the story. The year after my first visit, Kirin bought Mercian but for its wine business, not its whisky. By that time, Number One Drinks, convinced of Karuizawa’s quality and potential had become its international distributor. When the news came that Kirin was not reopening the site, they made an offer for the distillery which was politely rebuffed. ‘What about the stock?’ they asked. After protracted negotiations, in 2011 they bought the remaining 364 casks.

I’d return regularly after then, the last time for an epic tasting at Chichibu (where the casks were stored) where the three distributors [The Whisky Exchange, La Maison du Whisky and Eric Huang from Taiwan] chose their selection. The day before was my final visit to Karuizawa, by then doomed.

‘I’m sad,’ its manager Uchibori-san said to me as we says. I was here for 50 years. There were over 50 of us here at one time. We had a cooperage, we worked three shifts a day. We made good whisky. It was a happy time.’ As we left we saw him walking back to the office and turning off the light.

Even then, there were doubts as to whether the whiskies would sell. It was a risk – an unknown distillery with no reputation and a relatively high (£100!) price point. Then, somehow, the cult status began. Maybe it was the same as artists only becoming popular after their death. Perhaps it was the beneficiary of a change in people’s palates and a greater appreciation for ‘old style’ malts. The distillery may have been demolished, but at least we had the whisky.

And now it is over – for Number One at least. The question was how to bow out? A final single cask bottling, some special cask that had been squirrelled away for this final farewell? A single cask is a snapshot, a single frame. Once In A Lifetime looks at the entire story – the high-extract and smoke of the 60s and 70s, the golden age of the ‘80s when the style became fixed, and the later years where American oak came in and a sweeter side emerged. A complete picture of the old distillery in all of its moods. Karuizawa cannot be replicated, no matter the claims made by other actors. It is gone. This is what is left.

And so it ends. A whisky which no-one wanted to one that the world wants and which, market forces and scarcity dictate, now only a few can afford. Hopefully there will be some bars or events where it can be enjoyed.

————————-

Karuizawa, ‘Once In A Lifetime’, (58.4%, 145 bottles, rrp £19,500)

Karuizawa, ‘Once In A Lifetime’, (58.4%, 145 bottles, rrp £19,500)

The colour of highly polished mahogany, it places you immediately in two places: a forest after autumn rains when fungal, leaf mould aromas are at their height. There’s woodsmoke drifting from an unseen fire. Then you’re in an old library filled with leather-bound books. Classical Karuizawa in other words.

As it opens further, so there’s fig, date, myrrh, hinoki, balsam and a veil of smoke which hangs over juicy fresh fruits which add purity, lift and energy. Rich, elegant and complex.

A thick, silky texture envelops the palate and though high in alcohol, the density of the flavours reduce any burn. This is best sipped neat with cold water in the side.

It starts relatively quietly, with some more dried fruit and liquorice that moves to blackberry, hascap, and the balancing bitter bite of Seville orange. Things become increasingly deep and dark with woodsmoke, resin, and very old soy adding a meaty element.

Towards the back there’s prune (old Armagnac), calamus, vetiver, then just as it seems to be heading toward ever-darker territory, a surprising burst of sweet, bright orchard fruits. The finish mixes Da Hong Pao tea with roast pineapple, mango and gentle smoke. Balanced, complex, resonant. Only at the end is the full story being told.

Available from The Whisky Exchange from November 2025 with other markets to follow.