The Weekly Mash, Friday 29th August

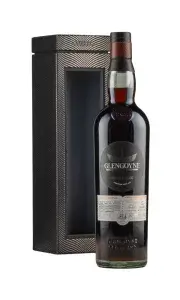

Hello me lovers… Welcome to another Weekly Mash. After last week’s smoky epiphanies we come crashing back to reality. Still, there’s a fine Master of Malt Speysider to please every pocket, plus a 25 year old Glenmo’, plus a Glengoyne from Hedonism that smells like a logging camp.

Falling Out Of Love With Malt?

It is hardly news that times are tough for whisky at the moment. While numerous theories as to why there has been a slowing have been offered, there has been little analysis of the underlying statistics. Thankfully, by looking at the Scotch export figures for the first half of this year, Martin Purvis and Duncan MacFadzen (at their excellent Substack ‘Commercial Spirits Intelligence’) have done just that.

The figures show a 3% decline in shipments overall (1.5m cases/£500,000) compared to the same period in 2024 and a 22% (14 million cases) fall on the Covid-induced heights of 2022. It’s accepted that the plague years were a wild period of feverish excess and thre is an argument to say that what w are seeing now is simply a readjustment and a return to the more considered patterns of the years before.

This appears to be borne out when Purvis and MacFadzen looked at the longer term trends. Although first half shipments are declining, they are still (just) above 2019 levels. Value, they point out, is up a smidge year-on-year. Why the panic? Why the talk of doom?

Is the cause of distilleries closing or cutting production, reducing workforces, shedding brands, stopping education programmes a manifestation of blind panic rather than reason? Or, should the loss of over 10 million cases in four years worthy of concern? That can be answered when the headline figures are broken down by sector.

There is a commonly-held belief that Scotch’s growth has been solely driven by single malt, that we are in a post-blend world. Malt saved the category in the ‘90s and continues to do so. Single malt was the golden child. All you needed to do was put it in a bottle and it would sell. No longer.

Single malt still only accounts for 8% of the category’s total volume. The half-year shipments show that blends are stable, bulk has slipped by 1% while malt has seen a 12% year-on-year fall (a drop of 500,000 cases) and has declined by 2.7million cases since the heady days of ’22, a 40% decline. First half malt shipments are now at the same level as they were in 2016.

The major markets (USA/EU) are in decline, Taiwan is sluggish, China has turned off. This assumption of a mass switch away from blends to malt doesn’t hold water. Instead, it is bulk which is steadying the ship.

Why are people falling out of love with malt? It would seem that the ‘drinking less but better’ mantra which has guided Scotch for the past two decades (the period when malt appeared to be in the ascendency) is faltering.

It’s been a line which, though occasionally accurate, has also been used as a fig leaf to cover falling sales. For it to work as a strategy you need a increase in total consumers – they may all drink less but there are more people drinking more expensive whisky.

Less but better lay behind premiumisation. Is its time over? As I’ve said before, it depends on what you consider premium. The majors saw it as 25 year old plus. The public saw it differently. And so, like a broken record, we return to pricing.

Some of the price increases were as a result of fixed costs and a knock-on effect of Brexit. Tariffs will not help either, but as a friend pointed out, the median price of 21-25yo whisky has risen by £280 per bottle in the last five years.

You could argue that distillers were blindsided by what happened during the pandemic, but it was clear to anyone that what happened at that time was an unnatural change in consumption habits which would end when a degree of normality returned and everyone sobered up. The idea that the good days would continue ad infinitum displayed zero understanding of whisky’s history. It was always unsustainable. There had to be a Plan B.

Single malt by its nature is premium (the product of a single distillery, finite) so how do you balance that positive asset with the feeling that it is now unaffordable? Might it be that this 20 year cycle is also one of perception? Malt’s early adopters in the ‘90s are now in their 60s. Are we seeing a generational shift underway? Is single malt, though young in category terms now ‘old’ in terms of image? Dare we say that one reason for it not engaging with a younger drinker is that it’s become one note, boring.

Whisky is resilient, yes. The upswing will come. Whisky isn’t being rejected per se, but the figures suggest that malt has either lost its cachet or that the cachet has become enmeshed in price. If single malt is seen as elitist – the drink of the haves – and you are a have not, then one of whisky’s greatest qualities, its democratic nature, becomes damaged.

Even if there are single malts which offer great value (and there are), the image is that of a drink which doesn’t belong to you. And key to getting new drinkers is finding real connection and relevance. Drinkers, whether established or new, feel disenfranchised. Just blaming price hikes infers that if you lower prices everything will be OK. It won’t. Price is just one symptom contributing to the ennui.

Single malt’s smaller players are more exposed. As Purvis and MacFadzen correctly point out, the majors can pivot to supplying bulk and low-priced blends. This was backed up by one distiller who told me that, ‘the whole industry relies on trash at 3-year-old going to random markets for SFA margin – just enough to keep the lights on and the machinery from seizing.’ India is saving Scotch at the moment, but not by purchasing premium whisky, but increasing volumes of bulk.

The way out of the slump lies in changing the narrative – something which the best of the new distilleries have realised. . What does Scotch mean to people? Ask that question, listen to the answer. Yes, price will be a factor, but it is only one element. The days of ‘people will buy it, because it is Scotch’ are long gone. There needs to be not one reason but many, and the story has to be coherent.

——————————

In My Glass

The new range of own-bottlings from Master of Malt sport revamped and rather sophisticated livery. Prices though remain among the most reasonable in the trade. Chapeau! They kindly sent over a sample of this 10 year old from A Secret Speyside Distillery (40%/£34.95)

The new range of own-bottlings from Master of Malt sport revamped and rather sophisticated livery. Prices though remain among the most reasonable in the trade. Chapeau! They kindly sent over a sample of this 10 year old from A Secret Speyside Distillery (40%/£34.95)

It’s fresh, light, and nutty to begin with – think hazelnuts in foaming butter. A whiff of lemon flower hangs around, along with porridge oats and, with water, dry bracken.

The palate start sotto voce with some dusty malt which then starts to soften as if some sugar is being sprinkled on the porridge (which of course is not the correct thing to do). It reverses the usual progression of sweet to dry with the fruits – pineapple cubes (the sweets), nectarine skin – starting to build around the mid-palate. Some peach comes through on the finish. I’d add water – or lengthen it into a Highball to get the full effect. Super-easy drinking at a pocket-friendly price.

Glenmorangie Altus 25yo (43%/£520) is the newest permanent addition to the distillery’s core range. Starting life in the distillery’s ex-Bourbon barrels it’s given a secondary maturation in ex-Madeira casks.

Glenmorangie Altus 25yo (43%/£520) is the newest permanent addition to the distillery’s core range. Starting life in the distillery’s ex-Bourbon barrels it’s given a secondary maturation in ex-Madeira casks.

It has Glenmo’s massed fruits here concentrated by time into honeyed richness though it remains strangely shy. Water teases out yellow fruits and the appearance of a dessert trolley laden with pavlova (sticky meringue), fresh fruits and flutter of rose petal). There’s also a little more oak, though I’d keep things neat.

The palate is where it shines. Silky and slinky to start with stewed pink rhubarb, white chocolate, mint framed by a nutty, oxidised quality and gentle tannins. Stewed red fruits take charge later on along with some agave syrup, mango and kumquat. It finishes with a wake up of mace, black peppercorn and sandalwood. A discreet sophisticate.

In the Cupboard

Another retail exclusive comes from Hedonism Wines in the form of this Glengoyne 16yo Fresh Sherry Cask (59.3%/£285). Intense from the off with aromas on the musky side of sherry. It weaves its way between sweet and savoury with hints of leather, dark autumnal fruits, prune and scented wood which adds a almost smoky edge.

Another retail exclusive comes from Hedonism Wines in the form of this Glengoyne 16yo Fresh Sherry Cask (59.3%/£285). Intense from the off with aromas on the musky side of sherry. It weaves its way between sweet and savoury with hints of leather, dark autumnal fruits, prune and scented wood which adds a almost smoky edge.

It’s a big, aromatically powerful beast of a dram which kick into the palate with bitters and walnut. It balances rooty, dry elements with a light oiliness, incense, resin and a sweet touch of red fruits. It holds alcohol well allowing a complex layered finish that mixes bilberry, and redwood sap. I don’t usually add water to sherried drams for the reason that it brings out tannins, which is precisely what happens here. Keep it neat, but have cold water on the side. It might be pricey, but it’s rather special.

—————————

In My Ears

It’s been a heavy week of researching and writing which has required a calming (but not bland) supporting soundtrack. Steve Gunn’s Music For Writers fits the bill perfectly.