Extreme distilling: Arctic barley

Two casks sat close to the entrance of the turf-covered warehouse. Outside a fresh fall of snow had settled on the ice. The fjord a dull blue, sky lit with the pastel hues signifying the return of the sun after the long, dark winter. That night the aurora would crackle and flex in greens purples and pinks above our heads. Whisky-making is different in the Arctic.

‘Nature is both our biggest advantage, and challenge,’ says Aurora Spirits’ CEO and co-founder Tor-Petter Christensen. ‘The climate has an impact on everything we do. The seasonality of nature providing ingredients, the challenges of transport to and from our location, the high costs of acquiring materials, as well as the “smaller trips” of rolling a barrel up to the warehouse in the snow. Avalanches, landslides, slippery conditions and ferry closures. But,’ as he says with a smile, ‘our remote location makes us uniquely resilient.’

Aurora is the world’s most northerly distillery. Situated at 69˚N, deep in the Arctic Circle, 94km to the east of Tromsø, it was founded in 2015 with production starting the year after. The full release of its Bivrost whisky is scheduled for 2025, but until then there is an ongoing series ‘Nine Worlds of Norse Mythology’ showing the work in progress.

This is my second visit here and things have changed subtly, but clearly – as things should when a distillery is finding its feet. So far they have used a mash from Popino and Planet Nordic barley made at the local Mack brewery, but are now shifting to making it all in-house.

In the small lab, bottles of creepy looking moulds are evidence of work (alongside Spheric Spirits) with wild local yeasts and Norwegian farmhouse brewing yeast, Kveik which has been used for almost 1,000 years. [Kveik is an extended family of yeasts from 50 farms in Norway, each with its own strand].

With every decision, Aurora is strengthening ties to its location. ‘It could be said that we’ve shaped our process to the conditions of our environment,’ says Christensen, ‘rather than trying to force conditions with temperature control or other modern technologies.’

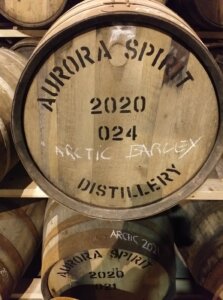

The yeast trials are one element, the other lies in those two casks with ‘Arctic Barley’ chalked on their ends. It’s not the place you expect to find barley growing but since 2019, the distillery has been working with local farmers to see what’s possible.

‘Barley can withstand the harsh climate here north and has been an important trade route for us for hundreds of years,’ ‘explains Christensen. ‘Before World War Two, barley was the preferred cattle fodder due to its resilience to the harsh conditions. After the war though, other grains took over.’

It’s not easy. Sowing can only start when the snow and ice leaves the fields. Most years this will be in late May, but a bad winter could push that back to late June. The intense short summer with continual sunlight means that harvesting could take place any time between late September to early October. It is whisky-making in the marginal zone, but if your aim is to make Arctic whisky, then barley and yeast had to be part of the equation.

Thankfully they found a farmer, Benjamin Hykkerud, in Alta, (210km east of the distillery) who had persevered for 30 years with growing feed barley. With funding from SkatteFunn (Research Council of Norway) and Innovation Norway, and research expertise from UiT / Holt research farm in 2019 the first trials were run with the Brage and Floy varieties. Even though crows ate all of the barley in one field there was sufficient to ferment – using a Kveik from the Hornindal Farm culture.

Yield, which most distillers obsess about, was not part of the equation. One ton made 810kg of malt, which produced 216 litres of spirit – four times less than a commercially available malt.

In 2020 they trialed a 6-row feed barley, Héder, (again fermenting with Kveik) because of its quick ripening and also short straw which doesn’t break in the harsh weather conditions. The same variety was used again last year, this time given a week-long ferment in the distillery’s new brewhouse. Now field trials are underway with Braga, bere and a Heder x malting barley cross.

The spirit is bright, barley-fresh, sweet, with a distinct citric/tropical note coming from the yeast and a softer, richer texture than the distillery’s make from the Mack wort. Every element appears to have been magnified. There is clearly something at work here.

It’s too early to say how much Arctic barley will be in Bivrost down the line, but the aim, Christensen says, is to get up to between 20 – 30% over the next few years.

They are not alone. Iceland’s Eimverk distillery has used local barley from its inception in 2009, partly as a challenge, says manager Eva-Maria Sigurbjörnsdóttir, to see whether it was possible and, if so, would it make a good spirit with a different taste. Ther was also a sustainability angle – to not be reliant on expensive imported barley.

As with Aurora, they use 6-row feed barleys (IS-Kria and Philipa) which add an earthiness, some grassy notes and an oily texture. While the climate impacts on sowing and harvesting, the variations between years, Sigurbjörnsdóttir says, has been turned to the distillery’s advantage.

‘The flavour will change depending on how plump the barley is,’ she explains. ‘And how plump it is will depend on the growing season, but the batch variations and the changes in flavour are part of the story.’ Rather than chasing consistency, the differences are what is exciting.

There is a wider discussion here, though. Though both distilleries are isolated – Myken, the nearest distillery to Aurora’s is 1,000km away (and is on an island 2 hours off the coast) – their experiences are providing fascinating opportunities for the wider whisky world.

‘The climate up here represent the most extreme in the world for agriculture,’ says Christensen. ‘The experiences we are making together with the farmers could prove to be good to share with other distillers in harsh climates – and we’re open for sharing and discussions.’

In Scotland in recent years there has been increasing interest in the landraces, bere barley, Scotch Annat, and Scotch Common. Landraces are genetically diverse varieties which over time have adapted to their environment and developed specific characteristics. They aren’t the result of breeding, but natural processes and are ideally suited to specific local conditions.

Logic would suggest that the shorter growing season, soil and climate of the west coast is very different to that of the east coast, where most of the barley is grown. If Hebridean/west coast distilleries are going to grow their own barley, then it makes sense to find out what is best suited to their conditions – and that might well not be the standard approved varieties. Bruichladdich has long used bere barley (grown for it on Orkney) while Raasay ran trials of locally-grown barley.

As well as landraces, trials are underway with early-flowering Nordic varieties such as Braga and Salome. As Dr Joanne Russell, senior postdoctoral scientist at cereal research body the James Hutton Institute [JHI] explains, they are primarily feed barleys, though also used for brewing. ‘They are 6-row barleys,’ she says, ‘and have a similar agronomy to the 6-row bere type, which is being used by a few distilleries (Bruichladdich). They are also genetically similar to the beres.’

So might these older Scandinavian varieties offer possibilities for Scottish distillers, particularly in the west? She was cautiously optimistic. ‘Earliness and a short time from sowing to harvest is what’s needed.’ She says. ‘In the Raasay trial Brage, Anneli and Iskria all matured, but the grain also needed significant drying to reach the desired moisture for malting.’ There was a note of caution. ‘We’re not there yet.’

Her mention of genetics touches on a key element in current barley science. There is a worrying lack of genetic diversity within the barley varieties which are being planted. Greater diversity is needed to help deal with climate change. ‘Most of our research is to identify novel diversity and develop genetic markers that can be used by breeders,’ she says. The JHI has sequenced the gene space of around 1200 barley accessions’.

Out of this could come varieties best suited to specific conditions, or crosses between landraces and modern varieties which would give higher yields but because of being suited to the climate need fewer inputs (fertilisers). A spin-off of greater genetic variety is greater flavour possibilities, but for any of this to succeed it has to first work for the farmer. A shift in the current model of payment per ton to payment per acre might help.

For Tor Petter Christensen, Arctic barley adds another dimension to Aurora’s operation. While all distilleries want to grow as a business, he argues, there is balance which needs to be struck between that growth and having a responsible, ethical approach.

As he says, ‘there should be a responsibility to our locations, not just an exploitation of them. To make a product that doesn’t reflect the unique conditions in its flavours and aromas is to make something which disrespects nature, the farmers, producers, community, and identity,’ There are lessons to be learned in the North.

This article appeared (in French) in Whisky and Fine Spirits magazine