Raasay Revival

There were beads of sweat running down our ever-reddening faces. Not because of any crisis, or misspoken words, but because the sun was beating through the vast picture window directly into our eyes, and the makeshift broadcast studio. Across the water, Skye was disappearing into a heat haze.

I was becoming concerned that the whisky might evaporate before we got a chance to discuss it, which would have been somewhat counterproductive since it was the first official bottling from the Raasay distillery.

Every first release is exciting, but this was special for personal reasons. I was lucky enough to be there (along with the entire island and other more worthy folks) on the day that the distillery was opened, and have returned regularly to see how the spirit was getting along.

It was clear from those encounters that the distillery’s co-founder and whisky-maker Alasdair Day was never going to take a cookie-cutter approach to his job. The washbacks have cooling jackets, as do the lie pipes on the stills. Both can be engaged, or not, to produce different characters – lengthening ferments, extending reflux, helping to create two styles of new make (unpeated and peated).

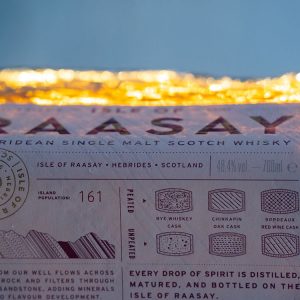

Neither has he gone down the now well-trodden route of maturing in first-fill ex-bourbon and STR casks. Instead, three types of casks – ex-Bordeaux red wine (French oak), ex-Woodford Reserve rye casks, and virgin Chinquapin oak – are used for both styles, then blended.

We chat though the samples. Chinquapin’s summoning of breakfast time at a classic American diner – maple syrup, fried banana, cinnamon toast, cherry cola and (in the peated expression) the savoury note of crisped-up bacon bits. Was that also a touch of warm leatherette?

The rye casks were slightly leaner, the unpeated lightly perfumed, with grass, green apple and delicate juiciness; more mineral accented, vegetal and bright when the peat was involved.

The red wine has none of the smothering vinosity that’s become wearily commonplace. By allowing the spirit to penetrate deeper into the oak the coliur isn’t blush pink, but onion skin. Fruity, sure, but not a fruit bomb. The blackcurrant, plum, and rhubarb are balanced by spice. Woodsmoke and black cherry are to the fore in the peated. Each combination spins the new makes into new directions. Layers are created.

‘The aim was to make a whisky which was lightly peated with dark fruit,’ he says. ‘As soon as we had that as the objective, we could design our process and wood policy. I wanted to get complexity and depth at a young age through then blending the different styles and oaks.’

It’s in the blood. Alasdair is following in his great-grandfather’s footsteps. Richard Day had started work at the Coldstream licensed grocer J&A Davidson in 1895. By 1923, already trained as a blender, he owned the firm.

Alasdair had inherited an 1881 sales ledger which contained all of the firm’s blends and recipes. What started with a personal challenge to recreate his ancestor’s Tweeddale blend has ended up here, off the west coast, in the blazing sun.

To concentrate on those details is, however, to miss the bigger picture. Malt whisky has changed from the days when distilleries were there solely to provide fillings for blends. Although it is now a category in its own right, the established distilleries which have become malt brands have continued to make the style which they produced under that ancien regime. And why not?

New distilleries, however, with no need to conform to those old ways are free to make what they want to. The arrival of single malt is not only a paradigm shift in the market, but also in thinking.

That freedom of thought has to be based on the production of a whisky which cuts through the mass of other new arrivals from around the world. This new whisky has to be different. The question is how?

It could come from distilling, or maturation, and also from an examination of the idea of place. When new, the ‘why here’? becomes more relevant to the story, and the answer lies in a deeper understanding of location. A new distillery becomes part of the place. ‘I am going to make whisky in X,’ becomes, ‘X is helping me make the whisky.’

This is a part of the world which has suffered from chronic under-investment since the 18th century. Cleared, scoured, ignored. Beautiful, yes, but you can’t eat views. Now, whisky is reviving communities.

Raasay distillery’s staff are in their 20s or early 30s, and most have connection to the island. Many, like production director Norman Gillies. are returnees,

‘The distillery’s completely changed what is possible here,’ he tells me. ‘When I grew up here, the industry was the fish farm, the ferry, and Raasay House, but there was no scope to go beyond a certain level. You’d have a steady job, but no chance of a career.

‘I left Raasay because of that. I was away, working offshore for a decade in order to be able to come back to live here.’

He was subcontracted to do building work when the distillery was being constructed. Now he runs it. ‘There is no shortage of scope to what we can do here. You see the age of the folk working here. Now there’s a reason to stay and have a job where you have scope to progress.’

The distillery’s brought in more tourists, so that has meant a new cafe, craft, a busy restaurant in Raasay House. The distillery has rooms – and now a bar – the hotel is full.

This is what a distillery can do – and is something which is being repeated across the west coast – at Nc’nean and Ardnamurchan, Torabhaig, Harris and with three more distilleries planned for the Outer Isles is a trend which will continue.

Whisky is helping to repopulate the depopulated lands. Like the hazel and juniper coming after the ice age putting down roots, whisky’s roots also bind. It gives focus it helps give identity and, now, create a new community. It builds layers. This sense of place is also a sense of people, and their sense of place.

Raasay, R:01, First Release, 46.4%

Nose: There’s very gentle smoke among the sweet, slightly fleshy, fresh fruits, dry grass/green bracken and, in the background, a slight mineral note and touch of wet linen. Give it time to rest and some weight is added to the fruits (plum, raspberry), as well as peppery spice.

Water opens it up fully. There’s a greater sense of space and also depth. Its more herbal, but there’s also banana peel, black cherry, as well as a new, slightly charred, element to the smoke.

Palate: A very soft, sweet start with some green apple, and boiled sweets, with the red and black fruits working well, and the peat drifting along. There’s a succulence in the centre providing a lovely balance between the juicy, now cherry-accented fruits, and the sweet spices, with the smoke little more than the smell of a distant bonfire. Water adds softness but also length and shows the layering effect to its advantage.

Finish: Pepper, mineral salts, fruit skin, and light smoke.