A stride through time: Nick Morgan on Johnnie Walker

In case you hadn’t noticed it, this year is the 200th anniversary of John Walker & Sons. As part of the celebrations Dr Nicholas Morgan has penned a rather excellent book on the firm. There also a trio of new blends taking inspiration from the firm’s story. They’ve been tasted over here

Raymond Carver once write a selection of short stories entitled, ‘What Do We Talk About When We Talk About Love?’. I could ask the same question – what do we talk about when we talk about whisky? Is it the distillery, the process, the ratings, the writers/drinker’s opinions, the history, flavour, place, or the people? Can there be space for all of this?

Do we, in talking about whisky, become our own editors – leaving some elements out for the sake of simplification, or expediency?

Whisky demands that you talk about it. Its nature triggers loquaciousness. The question is how to find the best way to engage with people.

This is an issue for blends. At the recent Virtual Whisky Show, we held a provocatively-named discussion, ‘The Long Death of Blends?’ (the question mark was important) during which we worried away at the question of how to make blends relevant to people again.

Johnnie Walker’s gigantic brand home in Edinburgh (scheduled to open in 2021) is a statement of intent that it is time to start talking seriously about blends again by concentrating on flavour, stories, and people. This is something which Nick Morgan has done skilfully in his newly released history of the firm, ‘A Long Stride’.

It has taken years of diligent research (the man is, after all, an historian) to piece together a story which is not simply about business but about whisky’s human element, a task made more tricky I imagine by the inherent reticence of the Walkers in the early days of the firm.

‘The thrawn Walkers were very different from many of their counterparts,’ Morgan writes, ‘and these differences defined some of the core values of their business… they eschewed publicity and self-promotion.’ Read that and you worry that this could restrict the telling of the tale, but the book is anything but dour. Indeed, neither are the characters.

It is intriguing to discover that the dilemma over how to talk blends and blending is not a new thing.

We are so used to the myth that Scotch is the golden child of the spirits world, bathing in constant approval and growth that it may come as a surprise to some that, as Morgan points out, ‘an enduring suspicion that [blending] was synonymous with adulteration was to haunt Scotch whisky in both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries,’ to which I would add, and in some folks’ minds in the 21st as well.

This rejection is surprising, especially since we are creatures who are hard-wired to blend – having more than one item on your plate is blending, pizza toppings are blends. Rums and teas were blended (and popular before Scotch), yet when it comes to whisky this predisposition to mix and create something greater than the sum of its constituent parts is considered somehow wrong.

But the Walkers persevered – there’s that thrawnness at work – blending in the family store in Kilmarnock, building brands; a local, then national, then international business. Forming a style, creating a signature.

As someone who likes the people/flavour side of whisky, there’s plenty of insights here, such as the fact that the whiskies first made by the firm to be drunk as toddies ‘were not for the fainthearted,’ because the toddy serve required something with smoky weight.

When Highballs became the drink du jour in late Victorian/Edwardian times, so the Walker blend’s recipes shifted. Still identifiably ‘Walker’, but lighter. Part of the equipment on the blender’s bench in the 1890s was a soda syphon, to test how they tasted when mixed.

He gives us a glimpse into how those blends were assembled by the creation of vats each represdenting a flavour grouping: Highland, ‘North Country’, and ‘Plain’ as well as grain, and the weightier Campbeltown and Islay malts.

Though in possession of the largest maturing stock of Scotch, even at this boom time Walker remained a firm which eschewed promotion – though it was canny enough to have a square bottle with a slanted label and colour coding.

There was a stunning reversal of this Calvinist abhorrence of fuss in the run up to the ‘What Is Whisky’ case in 1906. Now was the time for Walker to embrace the modes of the modern world – a shift in thinking driven by the remarkable James Stevenson.

Morgan rescues from relative obscurity this embracer of advertising, a shaper of the whisky industry, ‘who wrote crime thrillers in his spare time…a hard-headed, keen business genius… and a loveable romantic schoolboy.’ Finally, in this tale of whisky and whisky people, Stevenson is given the credit he deserves.

It is he who persuades the family to be more open and embrace advertising. He hires advertising guru Paul E. Derrick to mastermind the creation of the Striding Man. ‘[Derrick’s] role and [the] discipline of thought he brought to bear in bringing Johnnie Walker to life were critical.’

In another example of correcting myth, Morgan gently steers us away from the tale that the logo was dreamt up after lunch in the Savoy by Tom Browne. The cartoonist was actually hired by Derrick to create a logo. In doing so, the two men ‘rewrote the semiotics of whisky advertising at a stroke’.

Though this is the history of a business, it is never dull. It tells of distribution deals and sales figures when required, but not at the expense of the personalities.

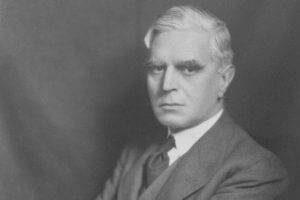

Take Sir Alexander Walker. ‘Tall and gaunt he once joked at his own expense that he was “the ugliest, sour-visaged, hard-mouthed devil to deal with”, a “Scotch Presbyterian constitutionally unable to smile,” who emerges as a visionary, a believer in quality, ‘a utopian, an idealist who genuinely sought to use his influence to promote better ways for society to be managed for the good of all.’

Although a veil is discreetly drawn over the ‘Special Trade’ during Prohibition (I suspect the heavy hand of Diageo lawyers may have been involved in that) Morgan is clear-sighted in his analysis of the downturn of the 1980s.

‘If there was a thread of an idea that held the brand together, it was the notion that it represented ‘masculine success (a somewhat generic category truth),’ he writes. ‘Although more than often expressed in ways that made both the brand and the category look stale, cliched, and out of touch with the new demographic for whom Scotch was no longer the first choice of spirits.’

The problem was that while the world may have changed, the whisky world hadn’t. I can’t help wishing however that I’d been around when home trade sales director Sir Hugh Ripley (who got the job after an interview consisting of a conversation about hunting, shooting, and fishing) was holding court in the ‘heavy cycle of socialising that was characteristic of the Scotch business at the time.’ A time when, ‘client meetings were followed by lengthy lunches, dinners, and nightcaps.’

At one point, Morgan speaks of ‘Walkerness’, the fact that once you had joined the firm you were there for life. You can only wish that the sales and marketing divisions in many of today’s whisky businesses still followed that model and that brand management didn’t simply mean control, but nurturing and believing.

‘Whisky is a remarkable drink and tends… to attract, like moths to a flame, remarkable people to its seductive orbit’. One of those is Nick Morgan.

‘A Long Stride’ is published by Canongate and is available through all good independent bookstores. Buy from them. They need your support.