Alasdair Gray, alchemist of hope

One of the questions we’re still asked about “The Amber Light” was why ‘other people’ (meaning those not directly involved in the whisky industry) were interviewed. It was because the film was about whisky’s role in Scottish culture and in order to do tell that story, we had to examine connections and parallels in music, and in literature. The ‘other people’ established the context and at the top of the list was Alasdair Gray. He’d had a serious fall three years before and was now wheelchair bound and I was unsure whether he’d be up to (and up for) helping us in this somewhat oblique approach. Amazingly, he was.

One spring day in 2018, we filed in into his Hillhead home following the calls of ‘Come in! Come in! The whisky people!’

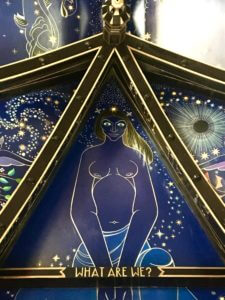

As the crew guddled about with tripods, lenses, mikes and booms, I looked around the room: the ancient computer, paintings on easels, high on shelves, framed on the walls, books everywhere. He sat at a slanting desk which was cluttered with new work. It transpires he’s working on a translation of Dante’s “Divine Comedy.”

We chat about Michael Scot, 13th century alchemist, astrologer, mathematician, theologian, sorcerer, conceivably the first Scotsman to distil and, according to Dante, the sole representative of the country in Hell, condemned to the eternal flames for the fraudulence of wizardry. A lad o’pairts, like Alasdair himself.

The son of a cardboard box maker, Alasdair studied at Glasgow School of Art before working as a scene painter and muralist from the late 1950s on, only coming to the public’s attention in 1981 with the publication of ‘Lanark’, a 600 page novel, 20 years in gestation and rejection.

After it came a deluge of other novels, short stories, plays, poetry, multiple political pamphlets, as well as an endless stream of art.

How to describe ‘Lanark’? It’s made up of four books arranged in different order, starting with Book Three, two of which are an autobiographical tale of Thaw, a young working class artist living in Glasgow; the other two an allegorical tale of a man who calls himself Lanark finding himself in a city of Unthank, which is also Glasgow.

Gray’s cities are like Joyce’s Dublin, Garcia Marquez’s Colombia, or Blake’s London. ‘Lanark’s’ arrival gave a different perspective on Glasgow, on Scotland, and what was possible.

In it, the character McAlpin says,

“Glasgow is a magnificent city… Why do we hardly ever notice that?”

“Because nobody imagines living here,” said Thaw…

“If a city hasn’t been used by an artist, not even the inhabitants live there imaginatively.”

Gray was that artist. For my generation, ‘Lanark’ showed us that we could write in our own voices about our own places. ‘Lanark’ helped stimulate music, the new Scottish art scene, and inspired a new generation of writers. As novelist Ali Smith wrote,“I came away from [a reading of ‘Lanark’] knowing that anything and everything were possible in writing. Scottish writing was in revolution and Gray was the heart of a literary renaissance which revitalised everything.”

Were you conscious that there was a movement when ‘Lanark’ finally appeared?

‘We weren’t aware of it ourselves until it emerged. By the time Canongate took the book on I’d become friendly with Jim, and Liz, and Tom, but we were set in our own styles before we met. We were amused to find we were being viewed as being a new Glasgow group. We only became a group because we were published round about the same time.’

You were trying to show there was more to Scotland than music hall songs and bad novels?

‘That’s what I initially thought. There had been a lot of middle-class visions of Glasgow, apart from ‘No Mean City’, but of course the most impressive Glasgow novel was by the author of the … it fails me, ohh…senility … you know … ‘Annals of the Parish..’

‘Galt?’

‘Yes, ‘The Entail’. A great novel about the Glasgow of the late 18th century. It’s not in quite the same class as [James Hogg’s] ’Justified Sinner’, but no Scottish novel is! No, what I realised was that there were great achievements that weren’t as properly noticed as they should have been.’

Which is the point. We weren’t taught them.

A little nod. He clasps his hands.

‘The thing was, when I was growing up there was no Scottish broadcasting. No-one ever noticed anything in Scotland in particular and as a result we rather took the view that there wasn’t much happening or could be happening.’ He gives a wee chuckle, almost to himself, looks at me out of the corner of his eye … ‘unless we made it happen for ourselves. Anyway, you want to talk about whisky…

What was your first memory of it?

I first had it socially on a Boxing Day when friends of my parents had arrived. They gave me my first purely social whisky and I found the sensation pleased me very much. Later, when I was at art school I was sometimes quite ill with excema so instead of going in I’d stay at home and have another whisky by myself. That’s how I got keen on it.

‘I’ve kept being keen on it and because I find it helps to make me stupid.’ A look over the glasses. He begins to roll his R’s extravagantly, a sign that this is important.

’I have a very active brain which keeps me awake for a long time at night, but if I stupify myself with whisky I fall asleep easier. I think it makes it easier for folk who find their intelligence a bit of a pest to stupify themselves.’

It plays quite a role in 1982, Janine [his 1984 novel about the sexual fantasies and despair of a washed-up alcoholic businessman]

‘Well, yes. There and in [MacDiarmid’s poem] ‘Drunk Man…’ In those two our man uses it to mainly to stupify himself.’

MacDiarmid was trying to revive Scottish culture and maybe the only thing left standing other than language was whisky, so he and other writers latched on to it.

He chuckles in agreement ‘That’s accurate. Fairly so …’

What do you think of whisky also bringing out that dark side in us – the old Scottish duality thing?

‘Och no, that’s an old idea, but it’s as much Germanic as Scottish. The Jekyll and Hyde notion is a simple one. No. The idea of us splitting into two is far too simple!” There’s a delighted laugh.

Another element is the way whisky is another way of defining areas of Scotland. You’ve written that landscape is what defines the most lasting nations.

‘If you look at it, Scotland’s like a large collection of islands jammed together. This was brought, forcibly, to me by a French film maker who said he’d come to the conclusion that Scotland was a collection of countries that were not quite a nation – that Glasgow had little to do with Edinburgh, the Highlands had little to do with the Lowlands and the Borders were distinct as well.

‘He seemed to think it was a good example to France which he felt was far too unified a nation at that time, whereas I thought he was defining a disease!

‘That’s the reason why I wanted Scotland to have its own independent government, so that the different bits of Scotland wouldn’t keep looking to London for leadership, but would converse with each other about what they wanted.

‘I had hoped Scotland would start setting an example to England of the type of social democracy that Margaret Thatcher started peeling away. This has not happened. I hoped the SNP and Labour parties would unite to restore the laws that had given me and so many Scottish writers and so many other people the chance to of a broad education which would also give them the time to look around and find the work that they were best adapted to do. But that did not happen.’

The amount of money generated in Scotland by whisky could be an asset to building a modern Scotland.

Laughs. ‘I agree! That’s it! I haven’t studied economics as closely as I should, but that could well be the case. There was a period when Glasgow was a city state it owned lighting, transport, bowling greens, housing stock. That’s all gone now.’

Is Glasgow in a better place now or is it just different?

‘It is different.’ He recounts a saga of him and collector Angela Mullane trying to create a gallery of his work in Riddrie Public Library ‘which was where to a greater extent my ‘University’ education took place’ around her donation of his best-known painting, ‘Cowcaddens’ which foundered due to lack of interest in the library board’s part, and of how a subsequent offer of a gift of a cityscape to Glasgow for free was rejected. ‘So Sorcha [his dealer] is selling it to the Tate.’

Does that make you an optimist, a pessimist, or a stoic?

‘Oh’.. immediately.. ‘a stoic .. certainly. No there’s no doubt of that! Pessimism is a way of putting up with a grim future. Optimism and pessimism are both ways of simplifying our response to the way things are going. Beyond a certain age, stoicism is the only sensible view to take, since it allows for hope.’

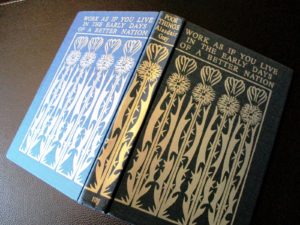

The quote most often attributed to him (though he always corrected them that is was actually from Canadian poet Dennis Lee) is “Work as if you live in the early days of a better nation.” It is that sense of hope and belief in humanity and community which runs through all of his playful, perverse, polemical writing,.

He’s not a writer about whisky. We barely touched on it in the short time we had, but it lurks there in an almost abstract way. His work reawakened creativity, and confidence, new ways of looking, doing, and making. It showed what was possible. You look at the new Glasgow with its galleries, restaurants and bars. Think of the minds behind it all, the people who have said, ‘we can do this’. In many ways it started with the hope he gave us.

He signs my copy of 1982, Janine, shakes hands. When I turn back, he’s back at his Divine Comedy. ‘I’m free from Hell now, I’m in Purgatory now’.

We had intended to go back and show him the film, but it never quite happened. On Jan 29, 2020 the news came that he had died. His work has helped make a better nation.