What Price Whisky?

£16 million for a cask of Ardbeg? Whether the declared price included 40% import taxes has yet to be divulged, it’s still a hefty amount of cash, but if someone is willing to shell out then it’s their business – which in a roundabout way is what surprised me about the transaction.

Private sales are famously done with a great deal of discretion – or as much as can be achieved in order to muffle the sound of the helicopter blades approaching the distillery. No names, no publicity, certainly nothing as crass as mentioning how much money changed hands. Bad form, old chap.

Although the Ardbeg sale brought it to the wider public’s attention, private sales have always been an element within every distiller’s business plan. From the casks sold to landowners in the 19th century, to the quiet trade between producers and brokers, or those sold to inject capital into a new distillery and, now increasingly as must-have items for the super-rich. Whisky will always available if you have the money. The Ardbeg sale just shows how much money you now apparently need.

The revelation of this deal, and the price paid, is the clearest manifestation of a significant recalibration of the category. The arrival of a growing number of high-net-worth players has resulted in distillers making available casks which would have held back for their own special releases or high-end blends.

Rising demand for whisky has also seen the sudden, and worrying, arrival of hard-e

yed City spivs and ‘experts’ of dubious credibility offering ‘investment’ casks. They promise impossible returns, and advertise stock which they either don’t hold (hoping that by getting a sale that the distiller might oblige), or which may not even exist – the whisky equivalent of Max Bialystock selling 25,000% of ‘Springtime for Hitler’ to his unwitting clients.

Distillers, who are increasingly concerned by the way this trade is developing, are restricting the number of casks which they make available to third party traders, which then has the effect of driving prices up. Established, reputable independent bottlers are caught up in this. There is less stock available, at higher prices, drawn from a shrinking pool of distilleries.

Seeing the reaction to the £16m cask was also lesson in how the narrative around whisky is changing. Provenance, flavour, quality, the fact that Ginger Willie (possibly) filled the cask of Ardbeg, is irrelevant.

In the 80s and 90s, Scotch whisky was almost killed by the commoditisation of standard blends. Now a form of commoditisation is taking place at the top end. All that seems to matter is the price, the return. Whisky or pork bellies. There’s no difference.

Who are buying these casks, and why? In a stagnating economy such as UK, the rich will conserve their personal assets rather than undertake private sector business investment (*). Whisky, it would appear, is seen as a secure bet, though how accurate are the returns which the investment firms are quoting? £16 million for one cask of whisky soon equates to vast amounts for every cask. It is ‘whisky’ which is selling, not the quality or reputation of specific distilleries, all of it built on promising the impossible to the gullible.

Do the people lured by these investment offers understand the risk involved, the cyclical nature of whisky, the gradings and desirability of distilleries? Not every distillery is an Ardbeg. Rather than being given an open assessment of the brand they’re interested in, its reputation, its performance, and the state of the market, they are being promised a guaranteed return.

Another factor lies with another group who desire to own an expensive object because it is expensive and fashionable. Whisky may be hot at the moment, but these consumers are fickle. If they are to retain their social (networking) status they have to be ahead of the game, and have the right brand on the bar of their super-yacht.

Quality, I’d argue, is of less importance – after all, anything can be gussied up to suit this particular requirement, be that an average single malt, or an ordinary rum. Pop it into a pretty bottle, hike up the price, wrap a spurious backstory around it and away you go until it is no longer Instagrammable, when those who are buying because of personal vanity (or lack of self-worth) will latch onto another glittery bauble to temporarily gratify their status-driven lust.

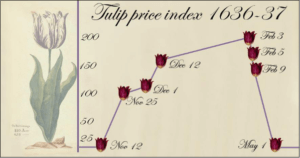

Whisky is on a shoogly peg (as we say) when it starts to over-commit in these areas. Neither are long term in nature, while whisky is. There are parallels with the ‘Tulip-mania’ of the early 17th century, when tulip growers, seeing an increase in demand, raised their prices. Then speculators arrived and up they went again. By this point it was no longer about tulips, but about making easy money from a commodity.

In 1637, the bubble burst. Those who paid top guilder couldn’t sell. Overnight, tulips became flowers once again. Nothing more. Those who bought into the craze late, hustled into this endless upward spiral with ‘guaranteed’ returns lost out. Hubris.

Let me qualify this. There are top-end whisky buyers who do want the story, enjoy being hand-sold something special, are looking for quality in the liquid – and will drink it. They care. The question is, do the people selling the whisky care as well, or are they just seeking that quick return?

My concern isn’t that the top end exists, rather that it is exerting a disproportionate influence on the category in terms of pricing and image. The growth of what is a small and esoteric part of a complex multi-tiered category has deluded some distillers into thinking that this is how the entire market is now operating. Everything is premium, so whack those prices up.

If a whisky’s asking price can be justified because of rarity, quality, and back story then I have no problem. If it is simply because of greed then it is dangerous for the brand – and category.

Those who love whisky know why it is special: a spirit whose quality isn’t defined by how much it cost, but the flavour, the people, and the place. That is a whisky’s true worth. It is what the cannier (mostly new) distillers understand. Build your reputation, keep prices reasonable, and play the long game. It seems a sensible approach. How many will follow that path is the question. £16 million suggests not many.

Resolution Foundation & Centre for Economic Performance, LSE, Stagnation nation: Navigating a route to a fairer and more prosperous Britain, Resolution Foundation, July 2022