The Weekly Mash, Friday 12th September

Hello me lovers. Last week I headed to Islay to join in the celebrations for Kilchoman’s 20th anniversary and got a chance to chat and reminisce with owner Anthony Wills, ‘the mad Englishman at the end of the road.’ There’s also a quartet of new drams from the chaps at Single Cask Nation.

It Pays To Be Bonkers

It was when I was standing at the entrance to Kilchoman that the old adage of policemen looking younger came sharply into focus. How can the distillery be 20 years old? (How can Arran be 30 come to think of it?) But it is. Time has passed and it has been good.

A bunch of hacks sit down in the rather splendid new lounge to hear Anthony Wills’ tale of family, perseverance, grumpiness, stubbornness, luck… and vision. Of how a wine merchant became interested in whisky, then pivoted to independent bottling.

‘It was the time when you could buy single casks and sell into emerging markets,’ he recalls, ‘but by the early 2000s the taps were beginning to be turned off. The old bottlers were going into distilling and I realised that owing your own supply made more sense. So I decided to build a distillery. We had enough money to build and run it for three years.’ He sees the raised eyebrows. Smiles. Shrugs. ‘I’m a risk taker.’

Decision made, next came the site. ‘It was always going to be Islay, or Campbeltown,‘ he says, ‘and Islay made more sense. Cathy [his long-suffering wife] had a long family association with the island, also Islay’s whiskies had a reputation, but everyone thought I was bonkers.’

He was told that Islay was full and couldn’t support any new distilleries, but his stubbornness told him otherwise, so ‘that mad Englishman’ began converting some buildings at Rockside farm at the end of the road to Kilchoman. Quixotic doesn’t come into it.

‘My thinking was also that ‘Brand Islay’ would help me massively,’ he continues. ‘It had a growing reputation around the world, but distributors didn’t have an Islay distillery on their portfolios. All the distilleries were with majors who had their own distribution.’

Build a distillery, make some whisky, age it, then sell on the back of Islay’s reputation into a growing peat-loving market. How hard could that be? Tough. Really tough. Any distillery needs sufficient investment to get through its first 10 years. Anthony had enough for three.

Underpinning Kilchoman’s story has been one of a continual search for financial backers who understood not just the vision but the long-term nature of this business. They needed to be bonkers as well.

Finances dictated that he had to get a whisky on shelf as quickly as possible. Anthony asked Charlie MacLean who might be able to answer his brief of a single malt which would hit the start of its curve of maturity early. ‘Jim Swan,’ came the immediate reply.

The Kilchoman Way was built on Jim’s template of clear wort, long ferment, slow distillation, reflux, high cut … and the best quality wood. It was finessed by the great John MacLellan who gave up his manager’s role at Bunnahabhain to take his chances on the other coast.

John passed away in 2016, Jim the year after. Their loss still hurts, and the mention of both brings Anthony to tears. He pauses, collects himself. ‘We couldn’t have done this without them. If only they could have seen this day and known their legacy.’

The word’s appropriate, for this has aways been a generational project. The formula for most new builds is to get the business set up, build a reputation, flutter your eyes at the bigger players, sell up and count your cash. ‘I never wanted that, he says. ‘This has always been about the family and passing it on to my sons and grandchildren.’

It’s worked. Kilchoman has prospered because of its quality. Its arrival added another facet to Islay’s smoke. Something more subtle, finessed, the sweetness more pronounced, less marine, less tarry. It spoke of the west coast, the machair, hot sand, fragile flowers, seashells rather than seaweed.

And now? ‘In 2017, we maxed out and had to double capacity,’ he explains, ‘but then in 2022 the door slammed shut. We were considering doubling again but that’s on hold. We’re not like others and stopping production though. We’re working 24/7.

‘In a downturn you go to maximum. You have to be brave, but when things improve you’ll be the one with stock.’ Still a risk taker then, but maybe not so bonkers after all.

Kilchoman’s story can be told in the comfort of the lounge but it only comes to life when you walk around. There’s bottles open for the party guests in every room. Most excitingly for a geek like me are the four samples of new make in the stillhouse: the first taken at five minutes into the cut when floral fruity freshness is everywhere, another at 20 minutes as smoke begins to trickle in.

The third, taken just before coming off spirit, is unexpected. Instead of there simply being a increase in peat, it seems bound in with fruits and oils. Kilchoman doesn’t emerge in a linear fashion – light to heavy, delicate to smoky, but in a subtle weave of elements, playing off each other.

The tale doesn’t stop there, so we pile into a trailer with general manager Islay Heads who is carrying a case of whisky for the journey. ‘We’ll make a few stops with a dram at each,’ he says. ’It’s also a test to see if you can pour and drink when on the move.’ It’s a bumpy track up to the first stop which, with Islay-sized drams already inside, seems a perfect metaphor for the Kilchoman story.

Another is poured when we get to the racked warehouse. A distillery exists in the present. The fascination lies in the act of creation. A warehouse speaks of past, present and future. It’s a gauge of health: are the racks full (they are), or empty. It shows options – casks types and sizes. It fills the senses and fills out the story.

Glasses drained, we bump off to one of the fields. Kilchoman is a farm distillery – it bought Rockside in 2015. Cattle and sheep are still run, but much of the land has been turned over to barley. Here are the roots. Literally.

Its 100% Islay is the purest expression of place in the range. Grown, malted, peated, distilled, aged and bottled on site, here the smoke is lighter, the drive more focused. We sip some as Islay explains the trials of growing barley in the west. Of how planting and harvest are dictated not just by weather, but by geese. No winter barley, plant in the spring after the migrants have gone. Get it off the field before they return. The season is short enough in the west, geese constrict it further. But KIlchoman does it because it’s the right thing to do.

It’s the next layer of the tale. You learn your flavour, understand your markets and learn about yourself, but everything you do is dependent on your conditions: who and where you are, how you deal with what life and location throws at you.

Glasses drained, we roll off to the machair above the bay. A final pour. Wind in the grass, birdsong, a chorus of cows, waves breaking. There’s nothing between this point and Canada. What does that do to your mind? Does the immensity of the ocean make you feel insignificant, just a dot on a dot in the middle of nothingness, or does the sea’s expanse reflect opportunity? Not at the end of the world, but its beginning?

That evening the great and the good gather to celebrate. Friends and family, Islay’s distillers, importers, suppliers… even writers. We drink, some sing, many dance. We all laugh and drink some more. There are tears, gossip, memories, tall tales, reunions and new meetings.

‘What have you got?’ I ask, idiotically, at the bar. ‘Everything,’ comes the reply. He’s right. Everything that was hoped for has come true. A dram of the 18 year old (who said Kilchoman was only good as a young whisky?) raised. Slàinte Mhór. Happy Birthday.

In My Glass

A clutch of new bottlings from Single Cask Nation arrived. So I tasted them.

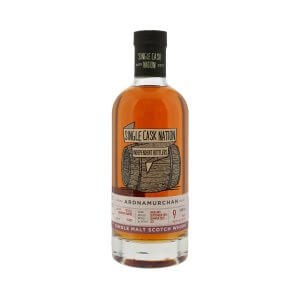

Ardnamurchan Peated 9yo (2015), Single Cask Nation (59%/£92)

Ardnamurchan Peated 9yo (2015), Single Cask Nation (59%/£92)

A first-fill Bourbon barrel has done its job adding not just colour, but an oaky, ice-cream like backdrop to the scented smokiness. It settles into a mix of the herbaceous (Timothy hay), oils, burnt heather root and with water, wet wool and citrus.The palate strikes a balance between linseed oil, peat and a sweet core which is rounded off by the wood which tightens things slightly towards the back. The finish is crystalline and fresh like a salted lemon. Water is required (for me at least). This reveals almond milk, honey and a lightening of the smoke, but doesn’t reduce the oils. A wee cracker.

Ben Nevis 12yo (2012) Single Cask Nation (56.4%/£92)

Ben Nevis 12yo (2012) Single Cask Nation (56.4%/£92)

The acceptance of Ben Nevis as a leading example of ‘old-style’ west coast whisky rather than same strange outlier has been hugely welcome. Here, the spirit’s been given a three-year secondary maturation in a #4Char American oak hoggie. While this might be make other malts quail, there’s enough muscle and weight here to cope.

There’s a sense of weight and solidity on the nose which leads off into caramel and butterscotch, hot sawn oak, a sting of leather, chocolate and sweet spice. The palate has all of Ben Nevis’ requisite thickness and pot still-esque lather (thanks Fionnán) plus dried apricot.

It starts to grip in the middle of the tongue, but the sheer weight of the spirit allows it to glide past. It softens a lot with water, but I like the full-fat impact

Glen Elgin 17yo (2007) Single Cask Nation (57.5%/£99)

Glen Elgin 17yo (2007) Single Cask Nation (57.5%/£99)

The question of how to balance spirit and oak runs through the quartet. Balance doesn’t mean perfect equilibrium, just having sufficient on one side to stop the opposite one from dominating.

This Glen Elgin has been given a six year secondary maturation in a first-fill European oak hoggie which is a fair length of time for a fruity, albeit rounded, dram. The cask’s presence is certainly there on the nose with, unusually, some tobacco leaf added to sultana and clove, while the distillery’s peachiness it behind. Water allows the wood to settle and things become generally more glossy.

The palate starts with the oak and a tannic touch, but again the distillery character comes to the rescue adding a gentle orchard fruit centre and some roast hazelnut. As it progresses you get fig jam and a little treacle on the end. Yes, it’s cask driven but there is balance.

Glen Spey 14yo (2010) Single Cask Nation (57.5%/£90)

Glen Spey 14yo (2010) Single Cask Nation (57.5%/£90)

Four years extra maturation in a first-fill American oak oloroso hoggie has give the nose the aroma of millionaire shortbread, clotted cream and a light wood oil element. Some oxidised wine elements the emerge. Water adds a nuttiness along with Weetabix doused in hot milk, walnut, spice, and orange peel. Sherry for breakfast? Why the hell not.

The sherried elements take the upper hand on the palate s well as toffee crisp (do they still make them, or am I showing my age again?) It has good energy, some raisin, walnut, dark chocolate and blackberry. With a little water there’s some dry grass and pistachio.

————

In My Ears

The extraordinary MacLean Brothers have completed their 9,000 mile, 140-day, non-stop row across the Pacific. We can all now relax and not worry about opening our mails in the morning to find tales of Lala being washed overboard, a marlin attack, storms, and fears of being driven on to the reefs of Tonga.

As it transpired, the most dangerous moment of the whole crossing came when they entered Cairns harbour and Jamie set fire to his bagpipes.

The fiddler Duncan Chisholm (whose work you should definitely check) and piper Ross Ainslie have combined to write a tune for the boys. It’s called Rose Emily, the name of the boat. All proceeds go towards the clean water for Madagascar campaign which, incredibly, has now raised £1million.