New Zealand Tour 6: Auld & NZWC

What was intended to be a hot off the plane, quick review of my New Zealand tour has, somehow, expanded in length and time taken to write it all down. Finally, though, we reach the end of the road.

Southlands-wards we go, heading for Rob Auld’s distillery. Michael has worked out that we need to get to a place with the unlikely name Nightcaps, and from there it will all become clear. There again, he’s not been there before and is relying on the car’s sat nav which, it soon becomes apparent, doesn’t know where we are either and is insisting on a street name in this mysterious town. I pick one at random, punch it in, and we turn off the highway on to white gravel roads.

After an hour, it transpires that this Nightcaps exists solely as an abstract notion, but Michael assures me that we’re heading in the right direction. Roughly speaking.

It’s a great drive through spectacular faming country, the road rolling along in great crests and dips. We start to treat it like a rally, drifting around corners, racing along the flat. ‘This is the least populated part of the country,’ he tells me. That’s pretty obvious. It’s now been 70 kilometres since we saw another car. Farms are rare.

Nightcaps has been abandoned, and we’re heading instead for Scott’s Gap, as that’s the town mentioned on Rob’s email. The satnav’s been turned off and I’m doing it by Google Maps and a sketchy signal.

Scott’s Gap turns out to be one house. Michael, ever the optimist, decides that he now knows where he is, and heads along Collie Road. It peters out in a dead end in the middle of a forest. I phone Rob.

‘Can you guide us in? I think we’re near. We’re in Collie Road’

‘Ah,’ he says, ‘not sure where that is. Just get to 100 Line Road and head along to the farm.’

The trouble with this is that Google Maps says there’s no such road. We turn around and continue in our vaguely south-westerly direction. I decide to send Rob a pin and try again. Inexplicably it shows that we hit 100 Line Road at the next junction. We guess that we should turn right and in a mile or so there’s Rob’s farm, which in a roundabout way, tells you that the Auld distillery is hard to find.

We drive through a museum of old farm machinery and outbuildings. Rob appears. Tall, shaven-headed and bearded, dressed in utility clothing, grinning. His wife Toni is shocked we’ve not eaten and conjures up a massive platter of meats and cheeses. We nibble away as the story unfolds, of when in 2005 he went into the whisky shop in Oamaru and saw a bottle of Wilson’s, then realised that his barley would have been in it. ‘That was when we began to think, why don’t we just do it ourselves.’

The Auld’s have been farming in New Zealand since the late 19th century, initially in Canterbury and here since 1924. Three quarters of the 200 ha is planted to grains. The distillery idea re-emerged in 2015 when Rob joined a Rabobank business development programme aimed at diversifying the business. ‘I figured, why not give it a crack?’

We go into the next room, where there’s an 80 kilo mashtun, whose contents are hand-stirred, and 60 litre fermenters where the wort spends a week, urged on by a mix of three yeasts. The stills are tiny, built to the sharp-angled Tasmanian style and electric heated. The wash takes 12 hours to pass, the spirit – which has a rectifying column that can be engaged – or not – takes four hours longer.

Rob is not only an optimist – you have to be to start up a distillery – but a seeker after what his patch of land can give. ‘This has made us question who we were as grain farmers and what to do with what we grow – and can grow in the future. All of our R&D is in the ground.’ Four strains of barley (Laureate, Black, Red, and Purple), wheat, black and white oats, rye, triticale, and maize have been trialed so far. More will probably follow.

‘It makes me ask the question, where is the terroir in whisky? Southland barley is big and fat. The yield is low but the flavour is rich. We’re growing the same cereal in the same paddock every year. Now, with a few years under our belt we can see the difference year to year. That’s hugely exciting. There’s a profile and there is a vintage.’

We settle into tasting some new makes (no mature whisky has been released yet). If the Laureate is hugely aromatic – fruit jelly – then Purple has an apple-y tartness and Black – which was introduced as a variety to give bread a longer shelf life – has a more wholemeal character, scone mix, darker fruit, and envelope glue.

The wheat is light, crisp and intensity, especially when compared to the soft, sweet oat new make with its mix of juicy green fruits, and a palate reminiscent of American cream soda. Black oats have the same doughy quality, with an earthier density, but it’s the malted oat that’s the bomb, toasty warm, creamy, unctuous, and succulent. Gladfield is doing most of the malting, but he’s starting to do some on site.

Wisely he’s distilled each separately to the same regime, but now comes a period of fine tuning where ferment length or cut points can be tweaked to disciver the sweet spots which speak about grain and place.

We start throwing about possibilities – a single malted black oat whisky, a mixed oat or barley mashbill, a Kiwi single pot still. It seems endless.

He hands me a bottle. Inside is a yellow liquid. It’s herbal, spicy, sweet, oddly familiar. He grins again. ‘Usquebaugh made to the 17th century recipe. Yes, we did use saffron to colour it. I also want to try and tell whisky’s story.’ Since what became whisky started as one made by farmers (or to be specific their wives) it makes perfect sense.

We wander out, towards the shipping containers which hold the casks – the local council is currently not allowing him to build a warehouse. He stops and looks around. ‘Aeons ago, all of this was covered by beech forest. Then a tsunami hit and buried everything under silt. You sometimes find trees which have risen to the surface. We’ve always used it as firewood but now there’s another possibility – smoking the grains. I want everything to come from the farm and the nearest peat is 400 metres over the other side of the fence.’ He winks.

As well as the need for a barrel store there’s plans for a larger distillery with significantly bigger stills, ‘but it all comes down to money.’ Setting up a distillery is a cash-draining exercise and needs long-term planning and understanding.

But, like I said, he’s an optimist and also has an important story to tell, namely that whisky is an agricultural spirit. ‘People know all about casks,’ he says, ‘but not about what went before. We’re an educational space to talk grain and whiskies that are seed to sip. We’ve had a thousand folks through already.’ Michael and I exchange a glance.

The drive east to Dunedin is less testing, taking us through the Hokonui Hills which played a significant, if nefarious, role in New Zealand’s whisky story. This was the haunt of the McRae family, skilled moonshiners who produced significant amounts of illicit booze after the passing of the Alcoholic Liquors Control Act of 1893 in which, at each general election, there was a vote on whether to allow more, or no new alcohol licences. For a number of years, the option of full prohibition was also on the ballot.

Local districts could also vote on whether to go dry, something which happened across much of the country. With a ban on new distilleries, the few existing plants strangled by red tape, and with pressure from Scottish banks threatening to withdraw financing for railways should Scotch imports fall, the result was widespread bootlegging in Hokonui. It wouldn’t be until the 1969 when the Baker family opened the Willowbank distillery in Dunedin that legal whisky distilling restarted.

The miles flick by. Dunedin announces itself at least three times before there is any sign of habitation. The old town, built on the profits of the 1860s gold rush has Victorian heft. Its architecture speaks of a confidence, which judging by the number of second-hand clothes and book shops and many other still shuttered post-Covid, has long gone.

Still, the combination of a university and cheap housing saw Dunedin become the centre of New Zealand’s post-punk music scene. Without it we might never have had The Clean, The Chills and the mighty Dead C. Silver linings under tarnished gold.

We go in search of a nightcap – but it proved as elusive as its namesake. The hotel bar only has dribbles left in its three-strong selection. We turn to our own emergency supplies. Always pack booze. And instant noodles. You never know.

The story of the New Zealand Whisky Collection is somewhat convoluted. In 1981, Seagram bought Willowbank, continuing to produce the Wilson’s blends and release a single malt under the Lammerlaw label. In 1997, the Canadian giant sold up to Foster’s. Three years later, the site was demolished and the pots and column stills were shipped to Fiji to produce rum.

The remaining casks lay, apparently unwanted, until 2010 when Australian entrepreneur Greg Ramsay bought the bulk of them and began to eke them out on to the market under the label of New Zealand Whisky Collection (NZWC). This time the malt was labelled as Milford. Mat Thomson also bought some in his early forays into whisky. Still with me?

Now, since 2021, whisky is being made once more in Dunedin, which is why Michael and I are outside the hulking, red brick Speight’s brewery next to a spigot which gives free water to anyone who turns up with a bottle.

It’s a modern brewery in an old shell and out the back above the keg line is a large room containing two Chinese-built stills with steel bases and copper necks, mimicking the original Willowbank setup. The brewery makes all the wash (all made from Gladfield malt) to the distiller’s spec, but the distillation is in the hands of either NZWC’s distiller Mike Byars or Cyril Yates, the latter of whom started work at the old Willowbank distillery aged 16.

None of the whisky is aged at the brewery. To find it, we head north 112 km to Oamaru. The countryside is, oddly, English – smaller fields, deciduous trees, a contrast to the Southland plains. The neatness only accentuates the shock when we turn into Oamaru’s main street with its extravagant columned buildings clad in the local whitestone, glistening with civic pride.

At its height, Oamaru’s port sent wool and frozen meat to the world. The money rolled in and the buildings rose. It was always a secondary port however, and by the 1940s trade had dwindled and the town was sidelined. Businesses closed, buildings emptied, people left.

Now though it’s a heritage site. Visitor’s come to see those grand buildings, view the blue penguins in their colony. Oamaru’s also the self-proclaimed steampunk capital of the world. It even has an official wizard. My kind of place.

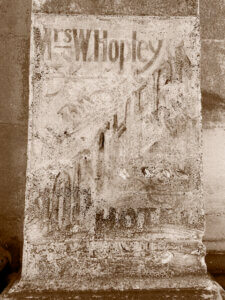

If NZWC has its way, folks will also come for the whisky now resting on the dockside in what seems at first glance to be an abandoned warehouse, though the red light over the door gives an indication to a former existence. Whorehouse to warehouse. Now there’s a story.

Inside, its high ceilings, peeling paint, exposed plaster, and abandoned bar reminds me of old Havana. The sense of gentle decay, of opportunities passing by, of colonial abandonment. And yet, here are the seeds of the town’s renewal. Behind the former brothel is a huge former scrap warehouse, now being filled with casks. It’s where Mike Byars is plotting the next stage in this convoluted tale.

Mike’s a Kiwi who returned here with wife Laura and family after a stint working at the Helsinki distillery. With Europe in lockdown, home seemed the best option. He’s another former winemaker looking at possibilities of casks, and blending. There’s a mix of sizes (from 55-litres to 278-litre barriques) and types – mostly ex-American whiskey of different types, but also French oak, and ex-wine.

Bungs are popped and we get stuck in. ‘We have two recipes using different yeasts which we give to Speight’s’, he explains. ‘The ferments are long as I’m wanting to get as much from the grain as possible. We’re gentle on the stills, otherwise the new make gets too chewy. You’ve got to be little cautious and not get too clean.’

There’s certainly none of that in the glass of new make he proffers which is sweet, lightly malty, but (red) fruit forward with just a light touch of oils.

An ex-rye cask mixes green acidity with rye bread and that spice. Intense but ordered. Ex-wheat gives a leaner result, with some chocolate creaminess and a distinct effervescence. It needs time to settle, but there’s promise.

A larger ex-bourbon cask adds the inevitable vanilla but it’s the mix of citrus zest and hazelnut that’s more intriguing. A 55l cask from 2021 is pretty much ready, all crème caramel, fresh banana then jellied fruits, and hibiscus. Here that new make oiliness is moving forward with the red fruits coming in. If this is a sneak preview, all is well.

The ex-wine casks add marzipan/cherry stone elements and fruits. They could be a secret weapon because Mike is less interested in single cask expressions – it’s the winemaker’s love of blending coming through. As he says, ‘for a winemaker it’s all about palate and nose. People think of age difference, but it’s really about blending and balancing.’

With the 55-litre casks peaking at 5 years, he’s already looking longer term. ‘The more neutral I can get the barrel the better,’ he says, anticipating the long-term results with refill. ‘But, if it’s too strong then I can always blend it in.’

Tasting with him it’s impossible not to be swept up in the enthusiasm of crafting something new and different. But he’s patient, understanding that the future cannot be made in 55-litre, oak-heavy increments. Whisky needs time and patience. ‘We’ve been making Sauvignon Blanc here for 50 years and we still don’t fully know what New Zealand wine is. Why should we already know what whisky is?’ he asks, not unreasonably.

That said, there’s a sense of this being a horse that’s not fully able to race as fast as it could. As a large brewery, Speight’s is rightly fearful of unusual whisky mashes ‘contaminating’ its beers. This means that Mike can only work off a restricted palette of malts – no speciality, no different grains, and definitely no smoke. There’s also the need to fit around the brewery’s own schedule which, if the whisky’s sales take off, could be problematic. But that’s for the future. What’s important here is that we have a town and whisky coming back to life.

We climb back into the car and head back to Christchurch. Circle completed. I fly home tomorrow.

What’s next for New Zealand’s whisky? This speedy runaround has shown the willingness of its distillers to experiment, to take risks even, to seek their own voice while also either consciously or subconsciously making it speak of where it is from.

There are hurdles. Winning over an often-sceptical home market is one, but with a population the same as Scotland, export is vital. That then puts extra pressure on the producers as it means that stock needs to be laid down now in anticipation of that uptick in sales in five to seven years time.

It is hard to build a business on single casks. It’s tough, it’s expensive, it ties up a ridiculous amount of capital, but this is a long-term business. The last thing any distiller wants is demand rising and only having half-empty warehouses and going on allocation.

Those firms early on the export market are not only selling their brand, but their country. That first taste of a ‘new’ country’s whisky is often taken as being representative of every whisky from that place. Quality has to be high, character has to be different, and not simply ‘nice’ because nice doesn’t sell long-term. Nice is interchangeable.

Any new whisky needs story, truth, transparency, and a quality which makes that first sip one where a new drinker thinks, ‘hang on, this isn’t just a whisky from a distillery in New Zealand, it is a New Zealand whisky.’

What those defining characteristics will be is what is exciting. The quality is already there, as is the local malt, the use of wine casks, the winemaker’s mentality, the variety of approaches, the self-reliant mindset. There is depth here. The next steps will be fascinating.

My thanks to all the distillers who so generously gave up their precious time to answer my often daft questions and most of all to Michael Fraser-Milne and Siona Collier for driving me around, and being the perfect travelling companions.