New Zealand Tour 1: Waiheke Whisky

I’m not long returned from a trip to New Zealand – first to the always amazing DramFest in Christchurch and then a tour around nine of the country’s whisky producers. I’ll be posting here about the trip over the next wee while, but let’s start at the beginning, with a visit to Waiheke Whisky.

Read on gentle reader …

Auckland’s towers retreated as the ferry to Waiheke island slid out of the terminal. It is warm, humid. Day trippers, blue sky, a scattering of islands, mini volcanoes, the bulk of Great Barrier island in the middle distance. Waiheke was a hippy colony, Colin Mairs tells me, growing crops of dubious legality, but great popularity. ‘Then the wine folks came and the hippies moved further out – off to Great Barrier and other islands.’

Colin’s a Scot now based in New Zealand, wearing many hats: writer, whisky salesman, experienced tour guide, and walking (or currently seated) encyclopaedia. We settle into a talk on the 30 min crossing, about Māori legends, the knotted history of language and misunderstandings, land grabs, and maps. It’s a taste of what’s to come

We’re met by Mark Izzard and Paddy Newton and drive off along tight, winding roads, the vegetation semi-tropical, small shacks housing meditation sessions, a taqueria, a fish and chip shop, glimpses of large stylish houses balanced by mangrove-cluttered creeks, and the ocean.

Our chat coming over had touched on creation myths, of how the trickster Māui hooked a giant fish which became North Island (South Island was his canoe). The creation stories of many new distilleries are similarly fascinating, their telling and retelling taking on the resonance of folktales. Many share similar tropes; friends on a trip, a fire, night time, bottles of whisky, an idea forming.

‘How hard can it be to make whisky?’

‘You’re bored with your job, you love whisky – why not just build a distillery?’

Others are purely about identifying a business opportunity. The romantic and the pragmatic. Whisky flickers between the two. It needs its tricksters as well as its more sober entrepreneurs.

Mark was an oncologist. London-born, he talks of days as a junior doctor in the Thatcher era, the burnout, mountain climbing, moving around the world, finally settling to practise in New Zealand, finally moving to Waiheke – and now starting a distillery.

Why? Because he liked whisky, because it was something that could be done here, an alternative to wine – you know, business reasons – but as he talks there’s the sense of something underneath, pulling him away from the stresses of being the person into whose hands people put their lives. He grins. ‘Some people have fancy girlfriends and Ferraris. I have a whisky distillery.’

Waiheke’s folktale emerges. There’s at least one fire involved, bottles, and friends. Not just Mark and his wife Ro, but a group including a paddle-steamer-dwelling savant called Eric (there’s no surname), a master brewer (Tony Denny), a much-garlanded winemaker (Paddy)… and a beekeeper (Richard Evatt). ‘Everyone needs a beekeeper,’ says Mark. ‘You know, someone to keep it real and grounded.’ Now Colin’s on board as brand ambassador.

You can’t be conventional here, or maybe, despite the island’s gentrification, it’s easier to not be. In any case, it would never be possible for that conglomeration of folk to take a straightforward path, something which snaps into focus as we wander down to a group of trees on the edge of a field.

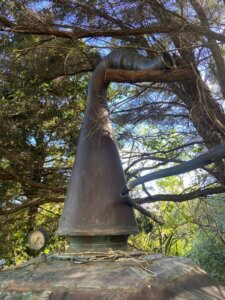

It looked like a mildly depressed elephant had left its trunk listlessly hanging over a branch, but any resemblance to an animal ceased when I looked at its body. Now it was a crashed spaceship, the capsule’s belly riveted and faceted, the entirety singed by entry into our atmosphere.

Stills aren’t meant to look like this. There are approved shapes – alembics, fat-bellied sensually curved pots, or severely columnar. There’s nothing in the manuals about geodesic domes. That battle with convention again.

Maybe you just need someone (in this case, Eric) who knows nothing about whisky to come in and say, ‘so the key is more copper? Why not make it geodesic?’ When you put it like that…

As Mark points out, a sphere’s surface to volume ratio is tiny. If copper contact needs to be maximised, a geodesic shape with its angles and planes is actually a logical direction. ‘There never was any thought about going to Forsyth’s and asking them to build a still,’ he says. ‘It was always, let’s make it and do it ourselves.’

I shouldn’t have been surprised. Only a few minutes before I’d seen a man drive a boat on wheels down the main street. People on islands do things their own way – partly because on an island self-sufficiency and self-reliance is built in. Islands also allow you to dream – and Waiheke is an island off an island.

‘Eric did the design, and made this beautiful paper model with the edges of each triangle numbered. Then we bought 67 square copper sheets. The only trouble was he forgot to put the numbers on the copper. It took longer than we thought to get it riveted together.

‘Then Paddy said that he loved peated whisky, so we got some malt from Bairds (Scotland, far away) and it was delicious, but we want to make New Zealand whisky, so we spoke to Gladfield (New Zealand, closer) about using local peat.’

The first runs took place at the Mudbrick winery where Paddy was working and winning his awards. ‘Mark then asked if I could do distilling full time,’ he recalls. ‘So Tony comes over shows me the process once, watches me do it, then leaves me to it.

‘I’m not saying there haven’t been mistakes along the way. The still imploded once, then the electric elements (used for heating) weren’t grounded so I was getting electrocuted, and the worm had such a small diameter that it would take two days to distil, but,’ he laughs, ‘the reflux was amazing!’ He seems remarkably sanguine.

The advantage with starting to make whisky in New Zealand is that home distillation is legal, allowing people to play, and find their style – while hopefully not blowing themselves up, or sending electricity through their body. It also explains why so many distilleries like Waiheke seem to emerge fully-formed, with mature product.

The jump to licensed production came after they won awards at the San Francisco competition. ‘I’ve gone for it,’ says Mark. ‘All my life savings. Borrowed a bit of money.’ They had to move from the borrowed space at Mudbrick and have ended up here at what they’ve called The Heke.

‘A mate of mine who brews bought it, and we came up with this idea to build a distillery, supply him with beer once a month, then also have a bar/restaurant/visitor centre. Waiheke gets 1 million unique visitors a year so we now have this chance to have a brand home for us and a home for all New Zealand whisky and turn people onto whisky instead of wine.’ Naturally, they’ve built it all themselves and, four years on it’s almost finished.

Any notion of them still wildly improvising is quickly dismissed as he walks and talks me through: how the separate conversion vessel and lauter tun and whirlpool give ‘super-clear’ wort, the half dozen temperature controlled fermenters with CO2 recovery systems, all running off the ethernet and using 100% renewable energy.

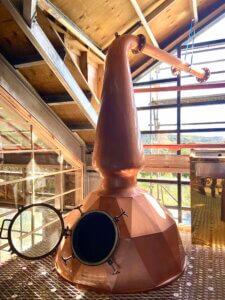

Naturally, there’s also a scaled-up geodesic spirit still – this time built by Speyside Copper Works. ‘Garry Fraser’s the driest bastard,’ says Mark. ‘I sent him a photo of our old still and his reply was ‘oh aye?’ That was it. Two words, but he and Derek Brewster reckoned it could be done by folding two sheets, then welding.’

It’s a slightly different shape – a half-dome (Mark calls it ‘more icosahedron’) but the result is the same – up to 25% more available copper. The worms have been replaced by external condensers. The character will, quite probably, change a little.

We’ve been sipping drams from the start: lightly-peated Moss – coconut, raspberry, cherry and red liquorice, subtle bay-leaf like smoke and soft weight on the palate; and its unpeated variant Sweetwater which shares the berries and rasps, but also kumquat, hot chocolate and mirabelle.

More bottles arrive when we sit down in the bar.

There’s Dyad (46%) that’s spent 6 years in ex-Bourbon then into cask which had previously held a Mudbrick Chardonnay which had been barrel-fermented and aged on its lees – which weren’t removed before the whisky went in. I almost say, no-one else does that, but stop myself. This is Waiheke, why not do it?

Maybe its the lees that are adding the nuttiness. There’s certainly an extra almost liquorous texture, honey, brioche, persimmon, lemon, and what seems to be a signature dry spice and a lingering mineral edge.

Another wine-finished example, Cantankerous ’06 (48%) finished in ex-Muscat is richer but more cask-driven. Actually finished seems the wrong term. Because of the high evaporation rates, what would be seen as finishing in cooler climates is more akin to second maturation here.

Two fortified wine examples are next. Seris I has had an Apera (PX) finish – all dried peach, pineapple, pot pourri, incense like smoke and raisin and that mid palate richness. Then there’s Peat x Port, the latter being a Petit Verdot wine whose ferment was stopped by the addition of spirit made from Tempranillo. Yes, I know. Tavel-like coliur, then acidity, rhubarb, fat, gently smoked.

Finally comes Bog Monster: heavily-peated malt aged in low charred virgin American oak for seven years. It’s sweet, yet earthy, rooty, touches of campfire with a eucalyptus/laurel note plus a resin/pitch pine element (maybe from the oak?) and a touch of Fisherman’s Friends.

All are gentle, and balanced. None are overdone. There’s also a shard palate feel to them, this layering of texture fruit and smoke.

’No-one had heard of New Zealand peat,’ Paddy explains. ‘Interestingly, as it ages it starts to pick up the manuka smoke character but we have no idea what New Zealand peat does over time and in these temperatures. We’ve been cutting as low as 55% to get more smoke, but maybe the new still we’ll get more of that peaty character coming over.’

Of course the aromatics are different. The flora is. Nee Zealand peat is comprised of sphagnum moss, wire rush sedges (Empodisma robustum) which maintains the anaerobic state of the bog, flax, shrubs (Myrtaceae which includes both manuka and eucalyptus) and Epacridaceae (heath). As in the UK, the country’s peatlands have been over-exploited by extraction for garden compost and restoration schemes are urgently required.

It’s a learning process. Distilling isn’t just set it up, push a button and off you go. As a distiller you have to always ask yourself the questions, test yourself and the equipment – which in turn will respond in some way. ‘This has been the time to make mistakes,’ says Paddy. ‘These stills will allow us to have consistency for the consistent releases – but also allow us to still play around.’

There are learnings from every batch and it will be refined and you find your own style?

‘That’s the exact point,’ says Mark. ‘We’re from here, we use local barley, we use local peat and wine casks. You have to explore what is around you.We’re not trying to be someone else. I mean, probably twice a week I think I should just go back to work and be a doctor not a twat, but it is a lot of fun.’

For all the excitement there’s still a basic financial requirement to sell the whiskies. ‘The first thing every person who came to our stand at DramFest said was, ’I don’t really drink NZ whisky,’ Mark says. ‘The biggest battle is with the New Zealand public. At this stage, all you can do is appeal to people who want something different. It’s only when you get the geeks that you start to create a loyal local market.

‘And it’s expensive,’ he adds. ‘A ton of peated malt costs £400 in Scotland. Here it’s $3200 [£1600] and then it’s $200 to get it to the island and the angel’s share is 10%+, but people still wonder why the whisky costs what it does.’ He smiles, shrugs.

This is a story of seeing connections, and is the antithesis of cold-eyed marketing. Rather, this is a story of why not? And letting a place come to you. Even after a short time on the island, there’s this feeling that this is what Waiheke does, act as a sort of green magnet for those of a certain mentality. Offshore thinking.