Loch Lomond: Alexandrian alchemy at work

Michael Henry opens the door and we enter a stillhouse unlike any other. There’s swan-necked pots in the far corner, but before them are hybrid stills made up of a pot still base with a straight neck containing rectifying plates: one in the wash, and 17 in the spirit, which also has a cooling ring. Of course it has. It’s all about reflux. It’s also about producing as many variations on flavour as possible.

As we’re in the Loch Lomond distillery in Alexandria (where Michael is master blender), you might think that those straight neck stills are Lomond stills. They aren’t. These were modelled on a design installed by Duncan Thomas at the Littlemill distillery in the 1950s.

Around the same time, Hiram Walker’s engineer Alastair Cunningham had a similar idea His design had three moveable baffle plates in the neck which could be cooled individually, varying the amount of reflux.

He first ran at the Inverleven malt distillery housed within Dumbarton grain distillery and was called a ‘Lomond’ still, presumably because Dumbarton is fairly close to the loch …Lomond stills also operated at Miltonduff ((making Mosstowie) Glenburgie (Glencraig), and Scapa. All are discontinued.

‘The characteristics of a swan neck pot defines the profile of the spirit,’ Michael explains. ‘The straight-neck stills, however, have flexibility and were created to produce a triple-distilled style in double distillation’.

By operating different cut points (high-strength at 85%, low at 68%) and levels of peating on the straight neck stills, he collects seven different flavour streams. Then there’s the new make from the swan neck stills to add in. Each release of Loch Lomond single malt is a blend of different distillates.

Engrossed in the stills, we’ve not even talked about fermenting. There’s no surprise that there’s different yeasts used, or that the minimum length is 92 hours to increase lactobacillus and esterification. Then, blithely, he says, ‘during silent season we just leave washbacks to get on with it. It’s a three week ferment.’

‘Funky?’ I ask.

“Oh yes… the wash is,’ he shakes his head and smiles, ‘but it distills beautifully’.

There’s more … of course there is. The malt side also has a Coffey still which distils a 100% malted barley wash (common practise in the 19th and early 20th century). The distillery asked the SWA if there could be a separate definition for this style, but the suggestion was turned down. So it’s ‘grain’, but not grain as we know it. That’s made at the site’s grain distillery. Confused?

With ‘grain’ now being used to label rye, oat and mixed mashbill whiskies from pot stills as well as Loch Lomond’s malt ‘grain’, maybe it’s time to re-examine the definition.

What could be interpreted as wild, random experimentation is in fact based on research set up by Loch Lomond’s former production director John Peterson. It is a self-contained, virtually self-sufficient (all it misses is a maltings) entity, a treasury of whisky knowledge whose work has barely been acknowledged.

That’s when it dawns on me. Alexandria. Not this one, but Egyptian city of legend founded by Alexander the Great in 331. A seat of learning, the home of a great library which was what we’d call a research centre rather than just a repository for scrolls. It was called the Mouseion (‘seat of the Muses’) from which we get museum.

A Greek enclave, Alexandria was where ideas were hatched, experiments took place, religions mingled and fractured. By the 5th century it was the largest city in the (western) world, a nexus of learning and knowledge, the centre of literature, science, philosophy and medicine

‘Water of Life’ author C.Anne Wilson in her investigations into early distillation places it as a home to the Dionysian mystery cult which, she argues, used distilled wine in its ceremonies, and, later, a home for Gnostic fire baptism ceremonies where distilled wine was ignited on the foreheads of acolytes.

Alexandria was also home to Maria Hebraea (Maria the Jewess, Maria Prophetissima) whose role in the early days of distillation, particularly at this time of the growing (and belated) awareness of womens’ role in spirits, seems to have been forgotten (or maybe I’ve just been looking in the wrong places).

She perfects various types of distillation equipment, invents the three spouted still (tribikos), and gave her name to the balneum Mariae, (bain marie) which is still used today.

As an alchemist she was investigating the nature of the building blocks of existence – proto-chemistry, chemical metaphors, occult practise, the interaction of matter with spirit, the genders of metals. Alexandria comes before Salerno, or Cordoba, even predating the refining of distilling which took place in Persia.

And now there’s a town in the Vale of Leven with the same name. Not named after Alexander the Great, but its 18th century landowner Alexander Smollett. It too has been a place of enquiry.

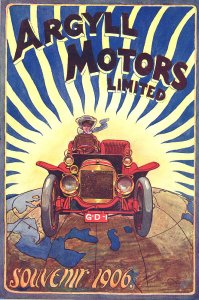

On the way to the distillery we passed a vast red sandstone Victorian palace which in the way of these things started life as the headquarters of a luxury car maker. Alexander (the name keeps popping up) Girvan’s Hozier Engineering started making Argyll cars in Glasgow in 1899.

He moved the business to Alexandria in 1905 building the palace with its marble interior, golden dome, and telephones. At its height it was making 3,000 cars a year – the biggest car factor in Europe at the time. It collapsed just at the start of WWI when the site was requisitioned by the war office and for the next half century it made munitions. It’s now a shopping centre.

Ideas seem to ferment here, thoughts and plan bubbling to the surface but never seem to stick. Instead there’s layering and repurposing. As one thing dies, another emerges. A place making. Before cars, torpedoes, or whisky it was cloth: cotton bleaching, printing, and dyeing.

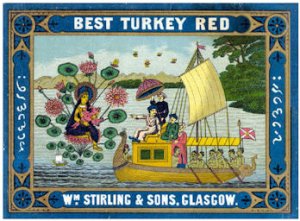

In 1897 The Alexandria Works (formed by the Croftingea and Levenfield sites) and other enterprises merged to form the United Turkey Red Company (UTR), making dyes for the textile factories.

Turkey Red (is it me or is that crying out to be a whisky brand?) was a bright crimson dye prized for not fading or running. The colour came from the root of the madder plant and while the process was long known in India, China and the near east, as with spirits it was late to Europe only arriving in the 18th century. (‘Turkey’ refers to the country not the bird).

Six years later, Loch Lomond built its distillery on the site. Some of the old UTR buildings have been repurposed into warehouses. Others sit empty. That layering again. (As a side note, during WWII the old Levenbank dye works was used as a victualling store for the Admiralty storing Navy rum for the sailors’ daily tot).

Loch Lomond was established to produce whisky destined for value for money brands, a high volume, low margin business. If that was the model it made sene to have everything under one roof.

Blenders also need a wide variety of flavours and texture. Loch Lomond took that principle, plus its own ethos of self-sufficiency and created the most innovative distillery in Scotland. When Japanese single malt appeared on the export markets at the start of this century, everyone got excited about how innovative the country’s distillers were with their multiple streams and in-house blended single malts.

Meanwhile, Loch Lomond was already doing the same. The only thing was, they didn’t tell anybody about it. Even now at a time when Scotch distilleries are, rightly, talking about ‘new’ ways of approaching whisky, Loch Lomond can shrug and says, ‘aye, but we’ve been doing that for decades.’ Michael doesn’t seem to mind. It’s just what they’ve alway done.

What has happened however is greater visibility and, thanks to a more enlightened wood policy ever grater quality. Loch Lomond now plays at all levels of the market and with Glen Scotia is building a new cult Campbeltown malt. As this new approach develops so Michael and blender Ashley Smith have a platform to show the flavour possibilities which exist. It’s not just the price range which is covered, but the flavour spectrum as well.

Think back to Maria in that other Alexandria: the questions, the refining and multidisciplinary learning, the flames on foreheads, those scientific investigations which examined the properties of material, in which one stream led to distillation and another to dyeing.

Then see how all of that ancient understanding of transmutation spread out across the world and through time, continually evolving, reshaping itself; one day ending up in the west of Scotland where it spreads again. Dye for high fashion, drink for pleasure and a modern Dionysian cult.

It is a human story of trial, error, success, and also one of a relentless belief in building. Loch Lomond, the Mouseion of Scotch.