Dyspepsia, apples and the problem with tasting notes

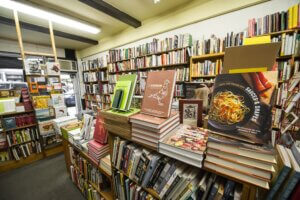

Up to Lexington/94 which, while not quite having the same ring as Lou Reed’s paen to heroin dealers, presents a far healthier option, it being the home of Kitchen Arts & Letters, a space crammed with every food (and drink) book imaginable. A sweet taste indeed.

Two remarkable titles left with me – a reprint of John Cage’s ‘Mycological Foray’ his essay/notes/photos/diagrams about chance, fungi, and foraging. It was accompanied by a slim, buff-coloured volume, an account of the ‘Proceedings from the First Annual Wild & Seedling Pomological Exhibition’. Now, that’s an irresistible title.

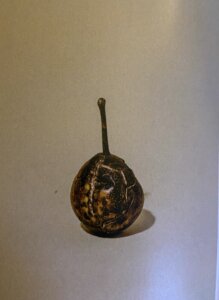

The exhibition, which took place in Ashfield, Mass. in 2019, was a show and tasting of 126 wild and seedling apples and pears from the US, 69 of which are featured in the book.

Like cereal crops, the genetic diversity of apples and pears has been decimated, the result of commoditisation and the perceived need for high yield and volume. The resulting homogenisation has left older, ‘uncommercial’ varieties clinging on precariously.

As with cereals, these elders: low yielding, oddly-shaped, non-conventionally flavoured, are ultimately more interesting. Diversity is good. I heartily recommend Dan Saladino’s ‘Eating to Extinction’ for more on this – and why saving endangered foods is vital for the health of the planet. The imperative to move away from monocultures and commodity thinking is is clear. The question how to restore balance is key.

In the pome family, as with cereals, one opportunity for change has come from the world of drink. Just as brewers and distillers are re-examining old varieties, so forgotten apples and pears are being saved by a new wave of cider makers who are moving the drink from being a quasi-industrialised product into one which is more closely aligned with wine or beer.

The book is gorgeous, each fruit photographed (by William Mullan), in such a way that it looks like a Dutch still life and is filled with evocative names: ’Arty’s Pal’, ‘Bitter Pew’, ‘Burning Church’ (a connection there, surely) ‘Bus Stop Ruby’ (which sounds like a Lou Reed title) ‘Gnarled Chaplain’, ‘Screaching Weasel’ [sic] and more.

What intrigued me most was the manner of their description. As well as details of where they grew, each was assessed for size, shape, form, skin tone, markings, flesh, sweetness, acidity, storage, and use [either eating or cider]. No scores were given, but there was a scale of ‘superlatives’, which ran from ‘good’ to ‘best’. There was no ‘bad’.

It was the tasting notes which delighted me the most. ‘Rich, hearty sweetness, nostalgic’ [‘Bern’s Sweet’], ‘dank notes of grape and pineapple’ [‘Heavy Cropping Red’]; ‘papaya seeds and vanilla with bitter qualities of thistle or milkweed’ [‘Hart’s Bittersweet’]

None, hiwver, could beat the description of ‘Bill’s Crab’ discovered by @pomme_queen (whose Instagram feed is a delight.) ‘Acid succulent and funky, a blend of gueuze stank and stomach acid. High and lonesome tannin. A challenge for fresh eating but…has its place in a cider blend.’

If you want to try, dear reader, hi thee thither to Brattleboro, Vermont.

It wasn’t just the honesty, and the shock of ‘stomach acid’ and ‘gueuze stank’, which are wholly descriptive, and simultaneously off-putting, understandable … and tempting, but the ‘high and lonesome’ nature of the tannins which intrigued me the most.

The term paralleled the ‘nostalgia’ present in ‘Bern’s Sweet’, as well as the high and lonesome sound of Appalachian (apple-achian)? music: of the Stanley Brothers, Dock Boggs, and Roscoe Holcomb. These are the sounds of tradition, of communities where people scratched a living. They are redolent with yearning, loss, precariousness, and defiance. As with apples, so with people.

The genius of the use of ‘high and lonesome’ is a perfect example of language taking a tasting note beyond the descriptive and analytical and into the poetic – not in the sense of being fanciful and pretentious, but using language precisely to convey multiple meanings.

I struggle with tasting notes these days. While I can see their usefulness, I’m also aware of their danger. My ‘apple’ in a whisky is not yours, my reference points are different. All a tasting note can be is an an approximation of one encounter. They are a compromise, but a necessary one.

The alternative is already with us. We can see it in countless Instagram feeds of people simply posing with bottles. That, apparently, is all the information we need to make a informed choice. We are under the influencers.

If notes in some form are necessary, then what is required is finding how they can work in a meaningful way. The key is balancing the analytical with accurate (if personal) descriptors, while also using language to speak of feeling and emotion. Where the whisky puts you is as important, if not more important, than what its mechanics are.

Another of last year’s books was Andrew Jefford’s ‘Drinking With The Valkyries’, a collection of some of his finest pieces about wine. It is a must read. His essay ‘Bags, Butter, and Biscuits’ nails the issue. Calling for notes which are, ’sensitive, nuanced, accurate, and innovative,’ (and brief), he adds that ‘it’s more interesting to hear about the particular way in which a wine is a wine, about its energy, its personality, its structure, it’s context.’

The context and energy, for me, speaks of where you are in the moment you taste. How does the whisky or wine, cider or beer change you. The emotional response is true communication. Go searching for the high and lonesome…

Kitchen Arts & Letters, 1435 Lexington (between 93rd/94th) kitchenartsandletters.com

@kalnyc

Matt Kaminsky, Proceedings from the First Annual Wild & Seedling Pomological Exhibition

Dan Saladino, Eating to Extinction, Jonathan Cape @dan.saladino

Andrew Jefford, Drinking With The Valkyries, Academie du Vin Library @andrewcjefford