Brittany rises

Brittany. Celtic redoubt, dolmens and menhirs, a land of buckwheat galettes and medieval towns, cobbles and harps, bagpipes and bombards, apples, cider, lambig, pommeau .. and whisky. Hence my trip to Lannion, only 20 minutes from our resting place on the pink granite coast, with its weird rocks shaped by wind and wave. A house of tides.

Thoughts of the late Kenneth White, expat Scottish poet who lived just down the coast, working out his geopoetics to the sound of gulls.

‘The questions is always

how

out of all of the chances and changes

to select

the features of real significance

so as to make

of the welter

a world that will last…

there is only poetry’

(Walking The Coast)

Lannion’s Distillerie Warenghem is today better known by the name of its whisky, Armorik, the Breton for Armorica, ‘the place in front of the sea’. France’s first dedicated whisky distillery, its story is one of discovering what is possible and of finding the right balance between the need to be local and specialised, but also international. It’s also model for what is happening in France as the country’s whisky industry builds in importance.

The distillery’s story starts in 1900 when Léon Warenghem began to produce liqueurs (including Elixir d’Armorique, a cross between Chartreuse and Drambuie). ‘It was typical of the time and place,’ explains its MD David Roussier. ‘At that time there were plenty of small distilleries making their own product and supplying alcohol to private customers so they could make their own macerations. All of that changed in the ‘70s with the arrival of the supermarket chains who wanted big brands at volume. The small players disappeared.’

Warenghem was foundering. In 1983 it was bought by Gilles Leizour (David’s father-in-law) who switched its emphasis away from liqueurs to traditional products. ‘This was a small local distillery making local products,’ David explains. ‘Our triple sec couldn’t compete with Cointreau, so Gilles started with chouchen (mead), fine (Breton apple brandy, aka lambig) and pommeau – the local apple juice/fine equivalent of Pineau de Charentes.

‘Because the thinking was about what was local and we’re Celtic, whisky made sense. Also, there has always been a love of whisky in France so the logic was that making French whisky could mean that we could be local, but also national.’

Gilles set to work getting ‘Scotch style’ pot stills. Rebuffed by Cognac coppersmith Paulho, he headed to Scotland. The first firm he approached was too busy, while the second, after accepting the commission, demanded payment upfront which was impossible. Thankfully they’d already given Gilles the design which he took back to Paulho. This time they agreed.

While the logic made sense, the reality was somewhat different. ‘We’re so into terroir and provenance in France, that it was hard to convince people that whisky could be made here,’ says David with a rueful smile. ‘In their minds whisky could only be Scottish or Irish.’

Needing distribution, also meant that they had to dance with the devil in the shape of the supermarkets. In 1987, the WB blend was launched with Armorik single malt arriving four years later. Supermarket sales gave volume but the margins were low.

France might have consumed huge amounts of whisky (it’s long been either the first or second largest export market for Scotch) but what was sold were low-priced blends taken as as apero.

By 2012 the strategy switched again. WB could never compete with the likes of Label 5, but could Armorik fit into a new whisky world where single malt was growing? If that was to happen, changes had to be made.

With Jim Swan on board as a consultant, the wort was made clear, the ferments extended, a second yeast added, and the stills reconfigured. The old lyne arms with their upward kick to add reflux were replaced with downward-facing ones. Fruit and weight were now the watchwords, a whisky which had the ability to age. ‘These days the whisky starts to settle when its seven,’ says David.

Now the barley (all organic since 2018) from La Malterie du Chateau in Belgium (with the exception of any peated which comes from Crisp in the UK). The difference from the old Armorik is noticeable.

Armorik Classic (46%) mixes sugared almond, sweet spice, soft fruit and a hint of agave syrup with a palate that flickers between green banana, dried apricot, acorn, and violet. Deiz (53.8%), a single cask release from this year has almost sherried depth with membrillo, dark fruits and a savoury, almost meaty weight.

The use of STR (a Jim Swan signature) for Deiz points to a more expansive approach to maturation. ‘The bulk has always gone into ex-Bourbon,’ David explains, ‘but it’s getting expensive and scarce, so we’ve started to work with a producer in Corsica who is making corn-based whisky. He only uses new wood, so we can get French ‘Bourbon’ first fill!’

Sherry casks come from Miguel Martin and as well as STR there’s other wines and fortifieds. The most fascinating, which ties everything back to those founding principles of the local, comes in exploration into the fine-grained local (Breton or Norman) oak.

He pulls a sample from one of these casks. Even after only five months the sweet yellow fruits have an extra liquorous quality, some rhubarb puree and the distillery’s new-style mid-palate weight.

We wander around, picking casks at random. ‘Ah, yes, this one …’ says David climbing up the racks. ‘It’s a 12 year old second-fill oloroso – on of the first that Jim filled. It’s layered, the aromatics heavy, citric, with rose, lilac, then brioche spread with apricot jam. It’s less sherried and more Sauternes-like with that touch of decaying fruit.

He pops the bung on a 14 year old virgin oak cask, ‘we just left it to see what might happen.’ While there’s definitely more oak, there’s caramelised fruits (Crunchie bars), that apricot signature, burnt sugar and a distinct rumminess.

A Pineau de Charentes from Landier filled in 2020 is intense, funky and highly concentrated: tropical fruits, sugar-coated cashews, while the peated Yeun Elez from 2000 and in an STR has typical juiced-up quality, alongside clove, marzipan, gentle smoke, soft fruit and an espalette pepper finish.

He looks at his watch. ‘We could go on, but there’s some caveistes arriving in the afternoon to pick a cask and I want to show you something else.’ We jump in he car and drive into Lannion. We pull into a courtyard echoing with the sound of hammer blows.

‘It’s the old town slaughterhouse,’ says David, ‘and look, ‘it’s even got pagodas!’ He’s not wrong. Abandoned, last year it became a independent cooperage (he is a part owner) along with Benjamin le Floc, who we find is the source of the din. Wielding his heavy hammer as if it were a feather, he has the combination of grace and power that singles out a great cooper. His waxed moustache also gives him the air of a modern Obelix.

His father was the last cooper in Brittany and when his business had to close, Benjamin had to go to Burgundy to follow the family tradition. Now he’s returned home and is another of the owners.

‘His allows us to do something which no-one else can – make our own casks,’ says David. ‘It allows us to experiment with local oak with different toasts, temperatures and chars. We’ve already worked out 20 parameters. We can make new casks, STR, and repair – and do it for all of the Breton distilleries. It’s a cooperage for all. I want the old knowledge to be preserved. In time, we can start to train.’

His plans don’t stop there. The plans for the site include a dedicated Breton whisky bar and a brewery which will also house a still where people can bring their apples for distilling. ‘It’s about community,’ he says. We can’t compete with Pernod-Ricard, but the whole point of Warenghem was to use what you grew and serve your community.

‘Malting and coopering have been industrialised, but if, like us, you make craft whisky you need craft casks, maybe also craft malt … and craftspeople.’

This principle of a focus on people and place runs through all of the world’s best new distilleries, but is given an extra tang in Brittany, partly because of the Celtic roots but also in what grows here.

In 1986, the late Guy le Lay, began to make whisky at his Distillerie des Menhirs in Plomelin. Like so many distillers his switch to whisky was driven by a decline in local spirits (in his case lambig and pommeau).

His idea was to make a Breton whisky using the region’s signature grain – buckwheat. His three sons Kévin, Erwan, and Loïg now run the distillery.

Buckwheat is a bastard to distil. Low yielding, can turn to concrete in the mash tun, and burn in a wood-fired still. It took hm 15 years to crack the puzzle, but in 1999, Eddu appeared. With its savoury aroma of new beech leaves, wakame and tarragon it moves into a strange, compelling mix of green mango and antiseptic on the palate accompanied by a rye-like oiliness. It’s a remarkable whisky, one which challenges your expectations of what this spirit can be.

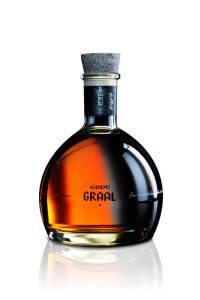

Last year the remarkable 21 year old Graal was released – the oldest ever French whisky. That long ageing has brought in rancio notes, honeyed tropical fruits and orchid, alongside spices fried in brown butter, with buckwheat’s drive as its spine.

Pleubian on Brittany’s Côte Sauvage is home to the Celtic Whisky Distillerie, founded in 1997 by Jean Donnay. Though now owned by Maison Villevert, Jean’s traditionalist principles have been maintained by distiller Aël Guégan. The barley remains Maris Otter, the washbacks are wooden, the pots are small, plain, and heated with flame, run slow with condensing in worms. The seashore location gives a salinity to the unpeated Glann ar Mor and peated Kornog.

And that is just scratching the surface. Brittany, like the rest of France is embracing whisky distilling, discovering in the same way as Kenneth White those significant features with which to make something which will last. It is what great distillers have always done. Poetry, distilling, craft are all ways of making something from this tangle of possibilities left on the beach.