Barbados Rum Experience: Part 2

By Day 3 I was getting used to waking at dawn to the sounds of racehorses being exercised in the ocean. Clusters of tourists would be up, already in beachwear, cameras in hand. People doing holiday things, the same as any resort,.

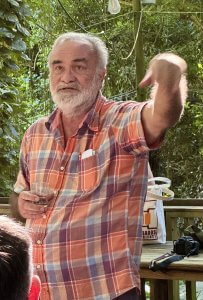

Then I recall what Mahmood Patel had said at Coco Hill Forest [see part 1] about how little of the money made by the hotels and resorts stays on Barbados, and also how tech/pharma multinationals will descend on the island, train up staff and the leave for a cheaper location – taking the staff with them.

Little has changed economically since those early days of sugar when the Caribbean sugar colonies produced the raw material, but all the profits were made in either the UK or North America.

Rum was primarily a bulk spirit until recently when Caribbean producers began to take control of their own production and create their own brands for export. This too is part of self-recognition and identity.

No longer the supplier, but the producer, and owner. No longer the off-shore business centre existing on the short-term whims of multinationals.

Rum, as Richard Drayton pointed out on Day 1, was a low wage, bulk product, produced by a highly skilled industry. The need therefore is to turn it into a high wage industry with export potential. Premium, not bulk. How to do this?

For agronomist Jacklyn Broomes (formerly Sustainability Manager of Mount Gay and now Research Manager at Barbados Agricultural Management), ‘it all starts in the fields.’

She and her team are examining cane varietals, crop and soil nutrition, pest control, agrobotany and sustainability. At the same time they are aware that, while to the outsider, rum seems to be the simple solution to a future profitable Barbadian economy, the island has to move away from the monoculture of cane.

The aim is to strike a new balance between utilising the varied benefits of cane – not just rum and sugar, but use of cane fibre, or as a feedstock for green electricity while simultaneously moving towards small-scale, multicrop farming.

Her talk looks at the work going into the breeding of new cane varieties, and encouraging farmers to plant a selection in each field (ideally no more than 25%) to cover potential problems.

It reminds me of chats with the International Barley Hub and the Bread Lab – scientists looking at the impacts of climate crisis, then breeding new varieties to build resistance. It’s necessary, but not a quick fix. ‘It takes 13 years to evaluate a new variety before release,’ she says, ‘and even then they might be scrapped.’

What of flavour? ‘At the moment we’re only interested in yield. The variety is lost in the mill. That needs a new conversation.’

The concentration on the field also opens up the possibilities of further diversification of Barbados’ rums with single estate releases.

A hiss of steam, the train judders, and off we shoogle up the cutting to the viewpoint at Cherry Tree Hill with its views along the wild Atlantic (east) coast. Then back on board, past stands of cane to St.Nicholas Abbey.

Built in 1658, it is one of only three Jacobean manor houses in the western hemisphere. Local architect Larry Warren has owned it since 2006. Not only has he built his own full size train set, but more importantly has returned estate-grown rum to the Barbados mix. It’s a trend rum shares with whisky – a willingness to draw from the past for inspiration.

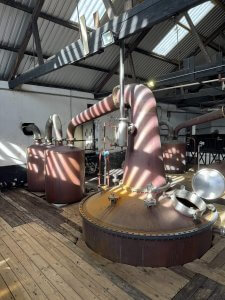

The millhouse grinds 350-400 tons of cane a year. The juice passes through a vacuum evaporator to turn it Ito cane syrup which is fermented, then distilled in a neat little Holstein pot and linked column.

The whole setup is part museum, part working modern distillery, an intriguing mix of agriculture, industrial heft, restoration and new thinking. The next phase, Warren tells us is to work on an archaeological project about the early days of the plantation and its enslaved people.

The Holstein set-up gives a high-strength, light-bodied rum which is aged exclusively in ex-Bourbon barrels for three years and then re-casked.

The exception is the ‘See Through’ which is new rum rested for three months in stainless steel. It has a fresh green/vegetal edge, plantain and sultana. The 5-year-old adds in nutmeg, grilled nut with a chewy coffee/chocolate edge.

We tried it, the 8- and 12-year-olds at standard bottling strength (40%) and higher (46% for the 5-year old, 60% for the older). All had added complexity with the extra boost. The 8-year-old with more tropicality, sandalwood, and light citrus; the 12 showing mature fungal elements and that signature chocolate touch.

We head down the hill to Mount Gay. This, the oldest of the island’s current producers was founded (as Mount Gilboa) in 1703 by John Gay Alleyne. Conceivably, rum was being made on the plantation even earlier.

It was bought by AF Ward in 1918 and in 1989 the brand became part of Remy-Cointreau. The Ward family retained the distillery until 2014, when it sold it to Remy which by 2014 had also completed purchase of the adjoining Oxford and the original Mount Gay plantations which are now being grown with regenerative practises.

Here again is a pot and column set up. Four sets of pots with retorts: One pair from McMillans in Scotland, the other from Fraga in Spain, one of which has a comically long lyne arm. Unusually, Mount Gay employs double distillation through its pot-retorts (most only do a single pass).

The stillhouse also contains a pre WWII copper Coffey still which was decommissioned in 1976. Left in pieces, it was reassembled from memory by distiller the late ‘Blues’ Hinds, who started it running once more in 2018. There’s also a larger column in a separate building, but we’re not allowed to see it.

It follows the Barbadian template of a column/pot blend, with the molasses (a mix of local and imported) being fermented with the distillery’s own yeast strain.

Trudiann Branker is the fast-talking, take no prisoners master blender in charge not only of the core range (Eclipse, XO, Black Barrel) but the Master Blender Collection, ‘where I’m allowed to play.’ The seventh release was her tribute to the much-loved Blues – made exclusively from his Coffey still.

The most radical step yet for the brand has been the launch of its single estate bottlings. All the cane was grown in the surrounding fields under Jacklyn’s eye, processed into molasses at the Port Vale sugar factory.

‘The reality is that Barbados cannot produce enough molasses to supply the industry,’ she says, ‘but that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t take that extra step and show what a rum made entirely from molasses from our estate can be.’

The molasses is then fermented for between nine and 11 days with a new yeast strain isolated from the estate. ‘We had five streams,’ says Trudiann. ‘Two were stable and one of those gave yield and also the congeners we needed.’ Then came a double pass through the ‘Scottish’ pot-retort (water is in the retort for the first pass, low and high wines from that distillation in the second)

‘It’s been seven years from start to first release,’ she explains. ‘The first release was a blend of 2016 and 2017 harvests, the second was from 2018, but 2105 is still in cask. Just wait and see!’

The former is fine, dry and on the salty side of mineralic with some light pear on the palate. The latter is sweeter, with more fruit and depth. ‘It’s a way in which we can preserve our history and is a signal of our commitment to our place and our people,’ says Trudiann.

The single estate, links to farming, working with agronomists and crop scientists, aligning with land, location and people, pulls Mount Gay, for so long the outlier in the Remy portfolio, closer to the thinking behind Westland, Bruichladdich, and Domain des Hautes-Glaces.

Foursquare too is turning to the land, cutting and pressing cane juice from its own fields then using wild yeasts to ferment. ‘It will be a true vintage rum, and a geographical link to the product’ Richard Seale had told us.

‘In normal production yeast is the machine that gives us control. With wild ferments the yeast is in control.’ It seems so not Richard Seale. He just smiled and shrugged. ‘It’s what it is.’ The use of juice element could be aged and bottled on its own, or also be used in homage to the earliest Barbadian rums (See Part 1).

It was Seale’s mention of ‘control’ that chimed with the underlying theme of the BRE. The issue confronting rum has always been one of control, or lack of it. Being in charge of your own destiny, your own brand, your own raw materials is one way. So, vitally, is having a GI.

How can you speak about a genuine Bajan identity if you do not have a clear definition for what Barbados rum is? At a time when all whisky-making countries are creating regulatory frameworks to help define themselves – and give consumers confidence, rum made here can still be aged, doctored and adjusted off the island and still say it comes from Barbados. Not having a GI simply perpetuates the colonialist view of rum.

On the final session all of the threads were tied together by Dr Tara Inniss, director of the UWI/ OAS Caribbean Heritage Network in her talk about the intangible cultural heritage. These are the warp and weft of a culture: language, art, customs but in this case also rum, and cane. The fibres not just of the plant, but of belonging.

‘It is a spirit and it moves people,’ she says. ‘That is how people will relate to it. There are so many fascinating points of this story that will resonate with people in so many ways. It is a new way of seeing. We’re not protecting it for the rest of the world. We are protecting it for ourselves.’

On the bus journeys I’d often find myself sitting next to Dr. Lennox Honychurch, artist, writer, politician, anthropologist, and historian of the ‘lost’ indigenous populations of the Caribbean.

He’d spoken about the last topic earlier in the week, but it was on our bus chats when he was pointing out chimneys, windmills and lost distillery sites that brought a different Barbados to life. An ever-evolving lesson of the lost, or mostly forgotten people’s history which needs to be rewritten. Rum’s story isn’t one of brands, it is of people. Image can be projected from the outside, identity cannot.

As Tara Inniss said, ‘cultural heritage provides people with a sense of identity and continuity. It is a generational response to place and history and is the people’s history of their crafts and traditions. They write it, not the outsider.’

The BRE is helping to start this narrative. It is everything that a spirit education programme should be about, and the fact that it is unusual in its approach only shows the paucity of true education and deeper thinking and connections in this sphere.

The cane grows, the forests are replanted, the roots grow stronger, watered by rum. As Tara Inniss says, ’this is the promise of our ancestors.’