New Zealand Tour 5: Scapegrace & Cardrona

Michael and I head out at 6am under a full moon. Dawn creeps, orange and scarlet, blues and indigo. Silhouettes of cattle and trees. Distant hills. Speeding along empty roads heading south. Breakfast stop at Fairlie, and my first breakfast pie. You can always trust a culture which respects pies. And soup come to think of it.

A pattern emerges. A progression of foothills, mountains pressing, then a pass, a plateau. Repeat. Laughing, swapping ever taller tales, reminiscences, whisky talk. We pass into Otago, seemingly the only car on the road. Merino nibbling dry grass, dead possums lining the road. One burst wallaby for variation. Lake Pukaki, its far shore fringed with dark blue mountains. This is open field land, a place to think as the landscape unfolds. The dead possum count mounts.

Five hours in we pull up at the Bendigo Gate on the shores of Lake Dunstan. Daniel McLaughlin and Mark Neal pull up alongside. ‘We’ll head up,’ says Mark.’ At the top of the corkscrew track, we look down on a half-built site. As they talk they conjure buildings from the air.

‘Over there’s the distillery’,

‘See that spot there? That will be the visitor’s centre.’

‘More warehouses will be over there.’

Scapegrace begins to take form. When completed, it will be the largest distillery in the country.

The idea was hatched 11 years ago by the pair who, with a drinks background, began to notice a shift to premium spirits – and the space for domestically-produced ones.

‘We were looking in this area and bought it as 36 hectares of dirt,’ says Daniel. ’No roads, nothing, just an airstrip for crop-duster planes. There was no power either, so a high voltage cable had to be laid.’

The usual protracted bureaucratic process completed, construction started in 2021. We head downhill to the completed first phase, housing the offices, bottling, and the first warehouse. The site occupies 36 hectares.

The next phase is the distillery, and after that the food and beverage side with bar, and cellar door. The tourism side was what drew them to Otago. ‘We’re round the corner from Cloudy Bay,’ Mark explains, ‘which itself brought other wineries to the area and after them came the crowds.’

Again, visions manifest themselves in the air. ‘A one ton mashtun there, washbacks over here, a pair of pot stills from LHS and a column for white spirits, and room to double capacity.’ The aim is for a slightly heavy make.

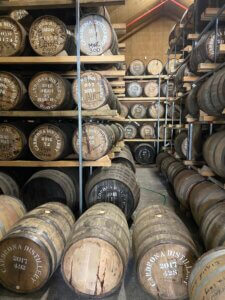

The warehouse is filling up with juice produced for them by Anthony Lawry at Workshops Whisky in Christchurch. The earliest distillates are in 50 and 100 litre casks, but now there’s been a move to 200 litre barrels. While there will be small amounts of ex-sherry, first-fill bourbon and Pinot Noir, the vast majority will be virgin French oak, which is a bit of a surprise.

New French oak is pretty assertive, shall we say. High in tannin, lots of spice, big extractives. Cognac producers use it briefly before calming things down in refill. In whisky you tend to see it used as a mix in blends, or for finishing, but full maturation is unusual. Still, the new whisky world is a place to try things out.

We sit down with a few of the current releases. All have punchy cereal notes, and the combination of a heavy young spirit, deep cuts, small casks, and bold oak means there’s plenty of elements slugging it out.

Revenant III has manuka smoke drifting through, Chorus II has some Jaffa cake, but it’s the Bulgarian oak-aged Timbre IV whose more gentle fruits and calmer presence shows what could be done. They should be though of as steps towards something rather than the complete story.

Scapegrace will change. The temperature conditions are different to Christchurch with colder winters and hot summers. The mash will be larger, the stills different, cuts can be played with, wood explored. That process that every distillery goes through to find that sweet spot between what you had in your mind and what the conditions give you. It takes time, but harmony can be achieved. There’s big thinking at work here.

Back in the car, Michael and I head north towards Wanaka, but cunningly swerve around the town as it’s show day and the centre’s rammed. Through back roads and into the valley, the sides of the road studded with rosehip bushes, the tarmac decorated by more dead possums.

The Cardrona Valley was another ancient route to the west for Maori in search of pounamu. In the 1860s, the same pathways were taken by gold miners including a large influx of Chinese – who plated the rose hips for medicince. Like Reefton, its the scene of a wave of humanity coming, breaking and retreating. Now tourists come to the snowfields.

It’s been five years since my last visit to Cardrona. What was even then a neat site is now fully planted and coiffed. There’s a sense that it’s settled into the landscape – and the community. It’s busy, maybe with refugees from the show. As we sit outside, a helicopter lands. Nobody seems surprised. Apart from me. It’s clearly a Kiwi thing.

Cardona’s the story of a dream. Of how, at one of those crossroads that we all come to in our lives, founder Desiree Reid began writing endless lists of what she might like to do. Spurning the attractions of crayfish farming, or mozzarella making, she set out to become a perfumer. Given perfumers need to know how to distil she went to a course hosted at Chicago’s Koval distillery which is when whisky began to sneak in to her thinking.

She returned to the States to the ADI conference, followed by a stint at Breckenridge in Colorado. ‘It’s all for perfume,’ she kept telling herself, but whisky won out.

Trouble was, there was no distillery back home in New Zealand. So she decided to build one in this valley. Travelling the world, getting advice, making contacts, finding a suitable bit of flat land that wasn’t on top of old mine workings. You don’t just need an idea to build a distillery, you need determination, and the ability to push on when it seems impossible.

Desiree is visiting friends, but master distiller Sarah Elsom is on hand (Cardrona, by chance rather than design, has an all-female workforce). With a BA in viticulture and oenology, she had a peripatetic career making wine around the world before settling back home – and began to make whisky.

‘The process is bedded in,’ she explains,‘so we’re at that point when we can play. I’m going to try different yeasts which are more tolerant to higher temperatures. We run a minimum of 72 hours and up to five days, and we’ve found that Pinnacle can struggle with that regime.’

A 1.5ton mash tun and six fermenters gives wash which has to be shared between the column still (for gin and vodka) and the whisky side. In its early days, Cardrona used Scottish barley, but has now switched to local supply.

‘I think that the cereal is more pronounced here,’ she says. ‘The malt is drier and slightly darker. It’s not a huge difference though – it just needed a bit of a wiggle at the top end of the distillation.’ Air-resting the stills between passes refreshes the copper, while slow distillation maximises reflux.

‘The room to really play is next door though,’ she says almost breaking into a run to the now stuffed warehouse. This is where she is happiest. Alive to nuance, finding different flavours and textures, seeing how this, still young don’t forget, distillery character is behaving. Finding the balance and harmony.

Her recent work has been working out the differences between the casks they’ve got from different Bourbon distilleries, Old Forester, Heaven Hill, and Four Roses. A taste of a 2017 from the latter had a lightly floral character and light spice (less than expected), over a sweet core and light cereal.

Cardrona has matured quickly. Quicker than Desiree imagined. A small sample from Barrel #1 laid down on November 5th 2015 is already mature with gentle dried fruits, fresh fig, walnut and more of an amontillado-esque delivery. There’s also that wet tweed note which you occasionally get in sherried whiskies – something that Alex Bruce and I both picked up on that first visit. There’s subtle power in this distillate.

Sarah is the second winemaker/distiller I’ve met on the tour, and I wondered if she felt that background influenced her approach. ‘I think my tasting vocabulary is still wine-focused,’ she replies. ‘I’m always thinking of texture and how it shifts. I see in shapes anyway, rather than words.’

Wine isn’t far away from her thought process. ‘Given where we are, it makes sense to use Pinot casks,’ she says. ‘I’m liking it for full maturation rather than finishing.’ I’d agree. A Central Otagan Pinot cask was beautifully scented with a mix of plum, fruit cask but still with Cardrona’s estery top notes, light spice and a little cherry on back palate. Thrillingly boisterous with great palate weight – that texture.

Another, this time from Mount Difficulty, was rich and elegant, with lighter oakiness yet more velvety tannins. That said, it’s got years to go. It backed up my feeling that Pinot is a clear signature for the distillery going forward. It just makes sense location wise and also in terms of harmony.

Cardrona’s early releases were called ‘Growing Wings’. Well, the distillery is now fully fledged and ready to leap off the branch. With more volume, it will be able to meet growing demand and move away from small-scale releases which thrill geeks but which can never give a solid enough grounding for brand building. An interesting boutique distillery or a medium-sized player? Greater understanding of the mature profiles means blending becomes another element in the offering. This next phase is going to be fascinating.

Back in the car, Michael and I head up the valley, the road narrowing as we approach the top of the pass. The world falls away as we look over to the serrated ridge of The Remarkables. Along there people are happily flinging themselves into the void. Far below a plane is descending towards Queenstown, our destination for the night. Beers are calling.