Port Ellen: Revenant distillery

This started as a tasting note for the new Port Ellen 40 year old. Then it grew. Stick with it, there’s some music at the end. The actual tasting note is over here.

And so arrives, somewhat unexpectedly, a new Port Ellen. Forty years in wood. Nine ‘rogue’ casks (four American oak hogsheads and five European oak butts) which we’re told, offer, ‘an entirely new dimension of flavour’, with ‘unusual flavour characteristics that stood out from the typical Port Ellen distillery character’. So, Port Ellen, but not as you’ve seen it before kids.

What’s the story here? To show diversity just as work starts on a new distillery which is being set up to create diversity; to bamboozle the geeks; to set up an alternative storyline – that Port Ellen was maybe never quite what you thought it was? All of the above? I’ve found that blenders like to tease you like that.

I’ve been peering into Port Ellen’s turbid pool from Rare Malts days. I’m not a completist though. Rather, I’ve watched and tasted, intrigued as it’s shape-shifted from unknown, to secret, to revered cult, then into a speculators’ dram.

My relationship has always been an ambivalent one. I’ve never been a true believer in its unparalleled greatness. It could be magnificent, but was it ever the best of Islay’s malts? Many times though it was austere, etiolated, barely hanging together.

Austerity and apotheosis

Given the ages of those manifestations, where was the one where air, oak and spirit were in harmony, where even was the astringent over-sherried monster, or the taste of fatigue where the elements had peaked then started to fragment and decay?

Instead, those chilly examples sat alone and palely loitering. I look back over the notes. ‘Tense’, ‘needs time,’ ‘unresolved’, ‘the sense of smoke massing out in the bay’. There was one so frosty that it was like arriving at a dinner party just after the hosts have been having a raging argument.

I called it Calvinist, a stern minister unbending in his belief, a Wee Free of a dram, a starched spinster.

Their colour shows little wood being in play. A desperate bottler would cry a whisky like this, ‘distillery forward’. Those of a less charitable bent would say, ‘lacking maturity and complexity thanks to knackered wood’.

How come that this distillery, the best set of Islay’s haul when whisky first boomed, one which was early to export, the one with the reputation, owned by the innovator, spent most of the last century asleep?

Port Ellen’s story isn’t about its recent apotheosis, it is why this prodigy disappeared.

Two consequences of whisky flourishing internationally in the late 19th century were the need for volume, and consistency, something which blends could offer.

The focus shifted away from the individual to the collective. Distilleries were at the service of the blenders.

It’s a model which works as long as demand is high, but when the see-saw of supply and demand tilts, so the smaller sites are imperilled. Sites whose flavour is a lesser contributor are even more exposed. Such was the case in 1930 when it first shut down, in 1967 when a boom in whisky saw it reopen, then again in 1983 when a slump closed it down once more.

Not a lot of smoky whisky is required if you require a suggestion of peat in your blend. And if you do want it, you’ll lay off active casks. Keep it fresh, use it young, place it in tired wood, maximise that smoke. We see it today in the growing gang of young, peaty whiskies. Smoky yes, but thin, edgy; pale-faced wee buggers with a blade in their hand.

When the crash happened in the ‘80s, DCL had a choice. Close Caol Ila, Lagavulin, or Port Ellen. The first was too big and had flex, the second had a high reputation. Port Ellen it was. In the wrong place at the wrong time. Once again, Islay’s awkward child didn’t fit.

The sacred dram

By the 90s things were changing. Single malt was rising and the peat wave gaining momentum. Islay’s big names caught it and headed off, but the maniacs kept looking, digging, fossicking around to see what else was around.

Out there, beyond the Italian bottlings of Laphroaig, the oily smear of Ardbeg, Lagavulin’s complex, restless weavings of land and sea, or the empyrean glories of old Bowmore, they found Port Ellen. The holy relic. Bottle as icon in the new orthodoxy.

True believers kept its liquid memory alive. Collecting, gathering, harvesting, learning, talking, attracting new acolytes. The cult grew.

What is belief? It goes beyond logic, comes from the heart, fuelled by hope, or despair. Belief is also blind. You hold it tight, you won’t let it go. In grief’s long trail, any failings are forgotten.

Call it cognitive dissonance, or simply a stubborn refusal to believe. A blurring of critical faculties as you are drawn into the pool’s peat-shrouded depths. The flaws are forgiven, the tragedy overwhelms the reality. Hagiography becomes the norm.

So, sure, it’s been given the benefit of the doubt. That’s cults for you.

You re-taste with that in mind. Look beyond the wet suit dripping with sea water, past the austerity and unripe fruits, the cold sea, the flinty tension, paraffin fumes and the harbourside paint shed. We’re not here to heap on blame.

You get sweetness and mintiness, preserved lemon, damp grass, green oiliness, manzanilla-like salinity, That saltiness like spume lifted from a wave; there’s white crab meat, smoked haddock, bloaters, tarry tea. It’s never relaxing, but an intellectual challenge.

Maybe that is what you want with a great malt. Not perfection, but a quality which nags at you, a dissonance rather than beautiful harmony.

You try to find the balance, but it’s elusive. You see how people become obsessed.

The revenant

Intriguingly, it is the Port Ellen lovers who have controlled the narrative rather than the owner. Until recently that is. In more recent times, it has ceased to be the relatively affordable oddity for the believers, to the plaything of speculators.

The fact that Port Ellen only distilled for 16 years out of the last 90 is all the information a new whisky investor needs. Closed distillery, finite stock, rarity = investment.

There’s a significant difference between a collector and a speculator. The latter is driven by return, the former by the chase, the discovery. Collectors are completists, obsessives, be it whisky, watches, rare books, antiques, or records.

The last is the one l’m most familiar with, so let’s stick with it. Crate diggers we’re called, always looking for the elusive, praising the hard to find.

Collectors are also driven into the weeds to seek out the weird, exhume the knotty, the perverse. That suits Port Ellen because it is not straightforward, there is always this uneasiness at its heart – that unresolved quality between that the oozing oils, sweetness, the smoke, and the spartan. Oh the irony that this awkward customer is the malt prized above almost all others by those with dollar signs for eyeballs.

Port Ellen is an improv musician, or folk singer snatched from pub back room to the main stage at Glastonbury. Once there they blink a couple of times and do what they have always done. So what if no-one claps?

As other malts began to be built as brands, cajoled and cosseted into shape, their distillery characters preened and gussied up, Port Ellen hung about outside, unobliging, pale. The revenant, returning from the grave, haunting the living. ‘I could have been you,’ it whispers.

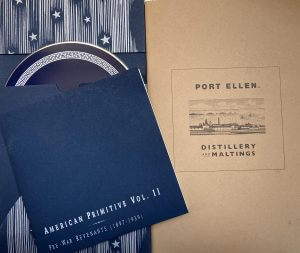

Revenant was also a record label set up by the late, great guitarist John Fahey and Scott Blackwood, which put out sets by the forgotten and difficult: Charley Patton, Charlie Feathers, Dock Boggs, Albert Ayler, utterly obscure pre-war artists like Geeshie Wiley.

Why didn’t people buy Ayler, or Dock Boggs? Why was Geeshie fated to only record six sides, of which only 10 copies still exist? Fate, bad timing, bad luck, playing a music that was at its heart just too eerie for mainstream success? Why do people (like me) buy it now? Because it speaks from the margins, it has a purity and is true to itself.

‘Raw musics, undiluted work from uncompromising artists, un-meddled-with, unexpurgated.. writes Blackwood. ‘Our Revenant empire, such as it is, is founded upon the proposition that if the masses reject or ignore it, it just may be worth looking into.’

How Port Ellen is that? The distillery as a forgotten box of records in the hardware store. The lost 78, the rusted pagoda on the side of the road.

‘What’s that?’

‘Dunno’

Most speed by, but some look closer, begin to wonder, taste, get lost in the oddness and contradictions. Now I realise that it’s those imperfections which intrigue, irritate, and keep bringing you back.

‘If I get killed, sings Geeshie Wiley, in ‘Last Kind Word Blues’, ‘please don’t bury my soul.’

The revenant is knocking on the stills and as an introduction to its third coming the blend of these nine casks, show what it wasn’t and, in doing so, show what it was – and maybe what it now could be.

There’s little smoke in this latest bottling. It’s a whisky where minerals, oils, rancio interweave, with tropical fruits, herbs, and salt playing above.

It’s mature, it’s balanced, gentle rather than austere, but at its heart there remains this intrigue, this sense of the ground shifting, the delivery somehow off-kilter. Port Ellen will never be orthodox.