The Weekly Mash, Friday 11th July

Greetings all, After last week’s Bordeaux-based epic, here’s some thoughts arising from this week’s quick trip to Ireland.. plus a gift from Thailand that was waiting for me on my return.

Time, the revelator

One of the many positives about traditional Irish pubs is their retention of snugs. Tiny rooms off rooms, sometimes with a door and reeded glass to give extra privacy. Places for trysts, private meetings, and contemplation – the ideal space to gather thoughts. Quiet afternoon places where the bartender operates in relaxed mode, where pints can gently settle and conversation exists primarily in nods.

The crew has been back in Ireland for the penultimate shoot for ‘The Amber Isle’, our look at the the country’s culture through the lens of its whiskey. Insights through the bottom of a glass. Now, cradled in red leather in one of the many woody nooks of Cork’s The Oval, pint of Murphy’s on the table, I start to try and make some sort of sense of the past two days.

In pubs like these the ghosts cluster. You become aware of the patina on the arms of chairs, ring marks on the polished table, the flotsam that’s cluttering walls and shelves.

The right place in other words to think about the story behind the sixth chapter of the Midleton Very Rare Silent Distillery Collection, the final runnings from the old distillery which have been sitting in wood for the past half century. Yesterday, Midleton’s Kevin O’Gorman had poured a sample in the warehouse where the casks had sat.

Drinking the products of silent stills can be exercises in nostalgia. The knowledge that each sip takes it closer to oblivion. Is it better to hold on and preserve in amber, or gravely consume? It can mean that tastings of this kind are like giving the last rites, a solemn wake with hushed tones.

This was different. This was a celebration, not a mourning. This was partly due to the nature of the whiskey itself. Vibrantly alive, mixing honeyed tropical fruits, nectarine skin and oils underneath which ran the deeper fungal aromas of whisky rancio.

It was this moment. Out there, the good folk of Cork were roasting in a heatwave, while in my nook I was surrounded by the smell of polished leather. The bright and the crepuscular simultaneously present. The whiskey had oranges and damsons, leaf mould, tobacco, sugar and pepper and the pot still oils, slinking into the mouth covering every inch, causing that energy on the nose to slow, then expand.

Yet what gave it resonance lay beyond these simplistic descriptors. It came from the people who had surrounded it. The whiskey had spent a period marrying in a cask made by cooper Ger Buckley and his apprentice Derek Cronin using staves from the casks which had held the previous five releases.

When a cooper finishes a cask, he stamps his mark on it. One of the staves carried Ger’s late father’s stamp, so he aligned his on one of the head pieces. Next to it was Derek’s mark.

The whiskey had been distilled under the eye of Max Crockett who passed it on to his son Barry. From there it was cared for by Brian Nation and finally Kevin. Continuity.

Whiskey isn’t fixed and things must change. The merger which led to IDL’s formation made sense, New Midleton made sense, as did the arrival of Jameson as a blend. When the Old Midleton distillery closed, pot still’s role in Irish whiskey seemed to dwindle. It was now a component rather than a standalone. However, change doesn’t mean eliminating the past.

I’d asked Kevin whether working in whiskey made him think about time in a different way. He smiled. ‘Yes, I suppose I do. We’re working to a 40 year cycle, so I won’t see everything I’m laying down today in bottle. We work for the future.’

In this way of thinking whiskey, strangely, doesn’t live in the present. It can’t be instantly reactive to trends in the way that, say, vodka or gin can. This might be seen as a disadvantage by the City, but you can only use what had been laid down years before.

This can be interpreted as being overly cautious, but it is to whiskey’s advantage that it has to take things slowly, that it offers reassurance rather than the quick fix of fashion. The trick is not to chase every sparkly bauble, but also keep things fresh. Change is necessary because you can’t be in thrall to the past. If you are, you die. At the same time, the past informs the future. Continuity and change in balance.

This was the right time to release this bottling. Single pot still is, once again, the heartbeat of the Irish industry. Here is proof of what went before, of pot still’s roots, of what might be possible once again. Another thread. Whiskey doesn’t work in eras. Its story is one of a continuum.

Kevin has been at IDL since 1998, starting in distilling under Barry Crockett, then in maturation with Brendan Monks. He’s not only covered both sides of production, but learned from the men who steered Irish whiskey through the rough times of the 80s.

He has experience, but he also has perspective, the knowledge that even when things might slow, the vision cannot narrow. That even in adversity you need to keep faith and look forward. It is what his mentors had done, what Max Crockett had done. These casks could have been blended away. They were kept because of the belief, the knowledge that their time would come. This bottling is a lesson.

———————-

A Musing (or not)

Were you to take the sad decision to close a distillery and lay off its staff on, say, a Friday would you then start up a series of ‘influencer’ dinners highlighting the whiskey you’ve just stopped making, the following week? I’m sure the notion of also launching a series of filmed chats with the distiller you’ve just laid off would be quietly shelved. Wouldn’t it?

—————————

In My Glass

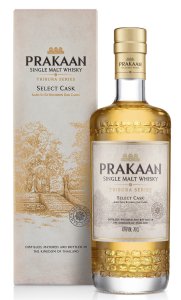

Here are the first three releases from International Beverages (InverHouse as was) from its Prakaan distillery in northern Thailand, to be precise in Kamphaeng Phet province. To try and ameliorate the influences of heat and humidity, the whisky is aged in two underground warehouses, each holding between 30 to 50,000 casks. So, not small.

Select Cask (43%/£65) is from ex-Bourbon and starts off with a mix of lychee, green peppercorn and a sweet, dough-like aroma. As it opens there’s some macadamia nut, cold whipping cream, and then some tropical fruits. It’s one of the sweetest whiskies I’ve tried: fruit syrup, guava, pineapple juice, and yuzu, with only the slightest tightening from the cask. Light-bodied and soft, all the action is concentrated in the middle of the tongue where there’s added melon and ginger.

Double Cask (43%/£80.00) Aged in both ex-Bourbon and ex-sherry, this is slightly fuller, though the fatness seen on the Select remains – a distillery character coming through? A ripe nose with some darker fruits, banoffie pie and brown sugar. There’s a shade more obvious structure. The palate is slightly shy, light- to medium-bodied and, once again, soft. There’s some vanilla sugar at play, a hint of dried tropical fruit and char, with a toasted /caramelised nuttiness on the end.

The trio is completed by Peated Malt (RRP £70.00). The smoke is there from the off, a bonfire that’s reached the comfortable, slow smoke, glowing ember stage. There’s a hint of meatiness and sweet leather alongside kumquat and fat fruits. The palate is also smoked which acts as an intriguing contrast to the tropical notes. Medium-weight, it too is focused on the mid-palate.

We’re clearly not in Scotland anymore – and that’s a good thing. Definitely worth a look.

———————-

In My Ears

Cork is a city that’s proud of its daughters and sons. Noticeable in our peregrinations around some of its finest hostelries were the many tributes to the great blues guitarist Rory Gallagher. Seems only right to have some of him here to get a bit of energy back. Just play the whole album…