The Weekly Mash, Friday 4th July

Pour yourself a dram, actually make it two. This is a big one…

WWF: Delivering A Dose Of Reality

As I write, the MacLean brothers , currently rowing non-stop across the Pacific, are confronting tricky conditions in the Convergence Zone, an area of confused tides, winds and rain. The going is tough. Last night Jamie reported he appeared to have been rowing backwards. It’s the perfect metaphor for what whisky is going through.

There’s over capacity, GenZ’s apparent rejection of alcohol, war, banks not understanding the long-term nature of whisky, spooked investors, economic pressures, low consumer confidence, tariffs.

The madness of Covid has also left psychological damage in its wake. We are more cautious, even fearful. The world is no longer safe and this is affecting the way in which we purchase and do business. How then do we navigate in this existential crisis?

Those, and other questions, formed the framework for the 6th World Whisky Forum [WWF] hosted by Maison Lineti held in Bordeaux’s Cité du Vin last week.

The WWF runs these three-day events every 18 months, alternating between distilleries in Europe and further afield. Their aim is to have open, frank discussion about issues facing whisky.

In each iteration, presentations and discussions take place around a central theme. This year’s was Building to Last, i.e. how to get through this rough period.

There were four panels each with three presenters and an audience made up of whisky people from 11 countries. Over the three days, a number of key themes emerged, the first being the importance of learning from history and how doing so could offer strategies.

I’ve probably banged on about this before, but there are very few people working within Scotch today who remember the crash of the 80s/90s and, more importantly, how Scotch worked its way out of that particular crisis. Few firms are therefore in a position to be able to make historically-informed decisions.

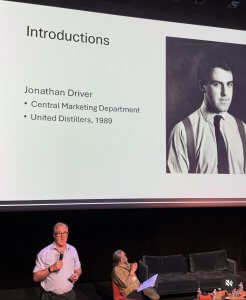

Thankfully, Jonathan Driver knows his history – because he was there. He spoke of how the crash was driven partly by complacency on the part of the major firms (DCL in particular), which had been lulled into a sense of false security due to the golden years of the ‘60s ‘when all salesmen had to do was take orders from customers.’

As now, global crises impacted on whisky: ‘stagflation, oil crises, the Vietnam War, and Watergate,’ shattering consumer confidence. The majors’ arrogance and inability to adapt led to an ever-increasing gap between demand and supply. The result was the aggressive takeovers and consolidation of the ’80s. He outlined how whisky worked its way out of the slump. By the 90s it was taking a lad from wine and seeing the parallels with single malt and, as importantly, talking to the consumer once more.

The lack of historical understanding was key to Fionnán O’Connor’s presentation, although he called it ‘the history of perpetual amnesia’. Using Irish whiskey as his theme, he punctured a few myths: monks weren’t the first distillers, the 1785 Malt Tax didn’t create single pot still, Bushmills was peated.

His point was that clinging to falsehoods has repercussions. The story becomes confused, messages are mangled and real learnings from history ignored as ‘the industry fills historical voids with bullshit, leading to strange, just-so brand stories’.

He urged the industry to embrace its true, complex history, rather than relying on jingoism and yarns. ‘By finding and telling the true stories of its past, the industry can ‘remember ourselves.’

One of his illustrations was of an old pot still recipe from Kilbeggan. After the talks, Alistair Longwell from Suntory Global Spirits asked him if he would be happy to share the recipe, ‘because we don’t have it and we could make it again.’ Knowing the past can help strategically and also creatively.

Longwell’s talk also touched on history and how the Japanese whisky crash of the 1990s and early 2000s led a period of introspection, culminating in Suntory’s decision to ‘totally rebuilt their distilleries and their processes.’

The same is now happening to its Scottish estate (which he oversees), manifesting first at Glen Garioch which has seen floor malting being reinstalled, direct fire replacing steam and changes in mashing, yeast and ferment parameters.

‘There is still room for innovation,’ he added, ’and while it might seem counter-intuitive, now is the time to add costs to make better whisky.

‘Enacting this can be challenging as it often means making decisions that run counter to how we’ve decided things in the past, for example by prioritising quality over cost or yield.’ Without understanding history you cannot move forward with any confidence.

The whisky industry has a tendency to be an echo chamber where everyone talks to each other rather than listening to other voices. Many whisky folk see their business and that of wine as being incompatible, yet as Jean-Michel Laporte, MD and winemaker at Chateau Talbot, demonstrated, the parallels are striking.

He set out the current situation in Bordeaux. Like whisky, there is overproduction resulting in 20,000ha of vines in Bordeaux being grubbed up over the past two years. ‘We have a surplus and there is an imbalance.’

This is coupled with the collapse of an over-saturated, over-priced en primeur market, loss of reputation and image, and an over-reliance on the top-end. The model of buying a wine two years before it was released and then sitting on it for another four to eight years before it is ready to drink doesn’t fit today’s consumers’ expectations.

‘The younger consumers want younger, fresher wines which are story-driven,’ he concluded. ‘The mid-priced wins have also suffered despite bing of high quality. We have to rebalance, restructure and clearly segment the market. It’s about transformation in the face of adversity.

‘What we need is innovation, diversification, and responses to consumer needs. There needs to be greater coherence between price and perceived quality, clearer segmentation, and direct sales channels. Bordeaux has always proven its resilience and capacity to bounce back,’ he concluded. ‘but today’s challenges demand bold changes.’

What then of new(er) players in whisky? J.J.Corry’s founder Louise McGuane set out the reality facing not just her business, but the new Irish industry. ‘Financing is a problematic,’ she said. ‘There are only two banks in Ireland with no understanding of whiskey, so it is extremely difficult to raise money – the banks wont lend. At times like this,’ she added, ‘debt is not your friend.’

One solution has been to sell abroad. As she put it, ’you export or you’re dead.’ Ireland has long had a heavy reliance on the US market which currently sucks up the 40% of its whiskey. The new distillers with low penetration and little cash also rely on Jameson to break the market for them. ‘Where they go, we follow,’ as McGuane put it.

Now, however, there is no space for small brands in the US’s three-tier system and with America’s second-largest distributor, RNDC pulling out of California, J.J.Corry is just one of 2,500 brands now looking for representation in a key market. Her conclusion? If you are a small brand don’t go to the US.

Scotch’s model during a slump was to discover new markets where whisky was building a following. This was variously Spain, Brazil, Russia, Taiwan. Now, however, all the markets appear saturated though McGuane believes she has found a bright spot – Nigeria. From there, she hopes, other African markets could open up.

The reality of running a whisky business was picked up by Penderyn’s CEO Stephen Davies who spoke of how today’s economic climate mirrored the challenges of 20 years ago. He was unclear whether the current state was a temporary short-term reset or the start of a longer-term phenomenon. ‘Cash is at a premium and we’ve got to question our whole strategy, he explained. ‘Companies must behave as if this is going to last and adapt.’

Picking up on Laporte’ point, he called for clearer market segmentation which he believed had been neglected in previous decades. ‘The thing that allowed us to move forward in the ‘90s was to have a greater understanding of the market. Without addressing consumer specifics, upward momentum in the industry will be elusive.’

In other words, it all starts with the consumer. The lack of connectivity is at the root of why whisky is seen either as old-fashioned and too expensive. If innovation is one way of getting out of the slump then it can only work if it is consumer-led.

‘If there’s one message in this presentation,” Driver had concluded, ‘it is that we lost connection with the consumer in the 60s which led to the problems of the ‘80s. We no longer understood what our consumer wanted.’ He urged this generation to embrace change, understand their markets, and never take resilience for granted. ‘Be interesting and interested in equal measure.’

That means stopping flinging new products into the void and hoping that something might work. Start to listen.

If there was a pachyderm wandering around the Cité du Vin, its presence was called out by Dawn Davies MW who opened her presentation with, ‘we’re in this shit, and we’ve got to get out of it. And partly we put ourselves here.’

Her point was that brands have been telling people what to drink not listening to what people are saying they want to drink.’ What is required, she argued, was the industry becoming proactive in its relationship with consumers and with retailers. As she said, ‘I don’t sell your whiskies. You do and you’ve forgotten how to sell.

‘As an industry, we’ve got to go out there and go old school. Knock on doors. Open bottles. We’ve got to tell customers why they want us, but in adversity there is always opportunity.’

As she pointed out, much of today’s dissatisfaction with whisky comes down to price and a skewing of focus by many distillers on the top end, to the detriment of the mainstream. Greater focus on expensive whiskies at a time when people are concerned with their finances is being wilfully blind to the realities of today’s market.

The top-end has a role to play, but it is not whisky’s saviour. It can provide a halo but over-emphasis alienates people, diverts attention and resources away from the area where it is still performing – the mainstream.

This point was picked up by Ariel Miao of the MsQ education platform in China who reflected on how in recent years the Chinese market was built from the top down with the ultra-premium brands building image and having a halo effect, thereby generating margins for broader marketing.

In reality, what happened was that the concentration on the ultra-premium segment resulted the mainstream being ignored – even though this is where the next generation of Chinese consumers are shopping. ‘Businesses need to balance their portfolios,’ she said. ‘And avoid this over-reliance on either ultra-premium or mass-market segments.’

All of this loops back to O’Connor and Laporte’s talk of the importance of stories. Every speaker agreed that engaging with the consumer was the correct strategy. That requires a narrative and it requires education, but how can you do that when marketing is dealing in wrong history, or education programmes have been cut? All firms now use AI, but what if the information you are feeding it is fundamentally wrong?

Here’s the kicker. Miao set up and ran Diageo China’s Whisky Academy (DWA). Over seven years it engaged over 2.6 million consumers and its 19 brand ambassadors delivered over 10,000 sessions across 40 cities. Last year it was scrapped.

‘Whisky education is not just about transmitting information,’ she said. ’It is about understanding the audience and creating immersive, culturally fluent experiences.’

This is the time to educate, to understand the history, then use it to talk and teach. It is easy to in the good times but more important in times of adversity.

Did we solve all of whisky’s current problems in three days? Of course not. Were there new routs and ideas? Yes. It is about re-engaging with the consumer and having historically-informed, flavour-driven, well-priced whiskies. It is about taking control of the narrative in this febrile, fragmented world.

As Ariel Miao said, ‘be like Kung-Fu Panda. Find you own moves.’ But find them….

My thanks to all of the speakers who attended this year. Not all are mentioned here but their insights will pop up over the next few months.

The talks from this year’s WWF will be on its YouTube channel soon

It will return in early 2027.

——————–

Roe & Co Woe

What has Diageo got against Irish whiskey? I’m increasingly convinced there is some atavistic impulse lurking within the company’s DNA reaching back to DCL days that manifests itself whenever a perceived problem emerges.

As part of the 107 lay-offs at the firm’s Irish business, its Dublin distillery Roe & Co has been mothballed. It’s actually been closed. The staff have been laid off including distiller Lora Hemy who, as anyone working within whisky knows is one of the most talented distillers of her generation.

Do you remember Phoenix Park? We spoke about it just the other week. Originally Dublin & Chapelizod distillery, it closed in 1877. DCL bought it in 1878, changed it to grain production, but closed it in 1921.

It was just one of a scorched earth campaign by the Scotch giant. Limerick’s Thomond Gate, became part of DCL when owner Adelphi joined DCL in 1902. It closed in 1919, while Dundalk’s fate was sealed in 1923.

In 1902, Derry’s Waterside and Abbey Street merged with Belfast’s Avoniel and Connswater, to form United Distillers Ltd. The firm was bought by DCL in 1922 to become part of a ‘large and united family with but one object, the overall good of the family itself.’

The Derry sites closed three years later, while Connswater never reopened after a fire in 1926. Avoniel was converted to a yeast site and closed in 1929.

Seven distilleries bought. Seven closed. Irish grain whiskey production virtually ended. Scotch blends rule. ‘Ireland is an irrelevance’ wrote DCL’s managing director William Ross. There’s family and there’s family…

Diageo’s return to Irish whiskey began in 2005 when it bought Bushmills from Pernod-Ricard for £295m. In 2014, it sold the distillery to Jose Cuervo (ow Proximo) for the same price to fund its expansion into Mexico. It then built Roe & Co. cost €25m which seemed a smart bit of business.

The going is tough in Ireland at the moment. The price of stock has crashed, Dublin Liberties has closed, Killarney is in receivership as is Powerscourt. Given that, Diageo’s decision to give up on a new, relatively cheap (for them) investment at the first sing of a downturn shows little faith in a category.

The decision comes down to looking at the numbers rather than stepping back and seeing what was being done at the distillery itself.

Roe & Co wasn’t a pilot plant, but a distillery where genuine investigations into what the plant could make and how it could be a commercial success by expanding the diversity of Irish whiskey. That takes time, but it was underway.

Business means making tough decisions rather than being emotional (like writers), but wasn’t this a chance to build a category and help it rise out of a slump rather than deepening said slump for all. The Waterford collapse has caused tremors across the industry. Ireland needs someone to stand firm and have faith. Someone like the largest distiller in the world maybe.

——————

In My Glass

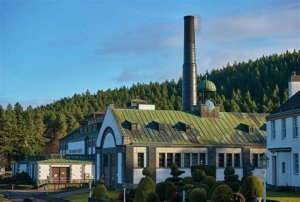

OK, let’s have some good news in the form of the first three releases from the mighty Tormore under its new owner Elixir. Under its previous guise, for me anyway, Tormore was one of those distilleries whose releases never quite fully showed its character in the best light. Now had blender Ollie Chilton and distillery manager Polly Logan have got under the bonnet and are finding out how to make this forgotten giant sing.

This trio of 10-year-old releases are limited to 1,500 bottles each (so get cracking), bottled at 48% and retail for around £60. As their name, Blueprint, suggest they are works in progress, indications of where Tormore is going. The good news is that the route being taken is a positive one. The A95 is clear.

Working back in terms of weight, the Toasted Oak (new oak casks given a long, slow toast and medium charring) is about structure.

It has the dryness which in the past was often overdone, giving a too abrupt shift mid-palate. Here it is integrated and serves a purpose. There’s nuttiness but sweetened into praline, then orange blossom, and a hint of char. Water eases things along balancing the fruits and the firmness, and revealing some spice.

The Cream Sherry also shows how the right cask can ameliorate the rigidity. This is about gentle sweetness and length: tinned prunes, hedgerow fruits, again some orange and a back note of toasted hazelnut, hessian, and violet.

If they are the support, then the Bourbon Barrel is the key player. Here is Tormore in a new light. There’s a dusting of icing sugar on a Victoria sponge, a whisper of creamy oak and purity of fruit (just-ripe apricot, William pear, gooseberry, lime, even a touch of hops. It’s medium weight, juicy and unencumbered by the cask. Delicious. Cannae wait to see what’s next.

——————-

In My Ears

What with all that, plus the heatwave, I need to chill. Here’s Pharoah Sanders’ Harvest Time, from recently (finally!) re-released album ‘Pharoah’.